Jacob's Well: Our Spiritual Songs II

As the seasons change, and times in Australia begin their focus on daylight and sun, I thought it is auspicious to return to a musical interlude for this week’s Jacob’s Well. We all know how music heals, lifts and transforms us. While we are divided by geography and circumstances, music always builds and strengthens the bonds that unite us. Here are some additions to the MYM Corona Comforts Spotify Playlist that might help you through the day. Don’t forget its address: https://open.spotify.com/playlist/3nvlMNqv8D0zr7sO1hqrrE?si=hrH9hy6BRGWu4p-Yi-LWug

OneRepublic- Wild Life

OneRepublic has just released a new song, ‘Wild Life’ and they are stealing MLF’s ideas! Fitting with this year theme, its ethereal reverberation and the iconic vocals of Ryan Tedder offer an uplifting pop song to start the day, or a retreat session!

I Surrender- Hillsong Worship

MYM Sydney has been recommending some great music in the last few weeks with its Music Monday choices. I love them all! ‘I Surrender’ by Hillsong Worship has been on repeat over this last weeks. Consistent in the style of the band and the genre, its slow crescendo-ing draws me deeper into prayer and love.

Meet Me in the Middle of the Air- Paul Kelly

We love this song, especially after ABC’s 7.30 report produced a stunning video of the song with the Melbourne landscapes. Paul Kelly (with the Stormwater Boys) is a music genius and a national treasure! “Meet Me in the Middle of the Air,” is a spiritual song unparalleled in his work, and in the Australian music landscapes. Paul Kelly has a complex relationship with religion, faith and God, but few people could produce a song so poignant, prayerful and moving. Based on Psalm 23, with the emblematic title drawn from 1 Thessalonians 4:17, this song never fails to stir the heart and touch the soul.

Any other suggestions for our spiritual songs collection?

Jacob's Well: Literature from Indigenous Australia

Reflecting on the input from Shannon Thorne from around the Well (from Marist 180, proud Kamilaroi man), one of the lingering thoughts for me is the invitation to keep broadening my education and to listen directly to the voices of Indigenous people in Australia. We can do this in the relationships we build with people in our communities, areas and networks. We can listen to Indigenous elders and voices on our radios, televisions, social media feeds and in written articles and editorials. We can also access the enormous library of books, fiction and non-fiction, that explore historical and contemporary expressions of people’s lives.

Over the weekend, I investigated a number of suggestions for contemporary literature written from Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander perspectives. Here are some of the recommended books to honour the voices, histories and cultures of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. The synopses are taken from other writers who have reviewed these works.

Our Home, Our Heartbeat by Adam Briggs, Kate Moon and Rachael Sarra

Adapted from Briggs' celebrated song ‘The Children Came Back’, this book is a celebration of past and present Indigenous legends, as well as emerging generations. At its heart honours the oldest continuous culture on earth. Readers will recognise Briggs' distinctive voice and contagious energy within the pages of Our Home, Our Heartbeat, signifying a new and exciting chapter in children’s Indigenous publishing.

Finding the Heart of the Nation by Thomas Mayor

Since the Uluru Statement from the Heart was formed in 2017, Thomas Mayor has travelled around the country to promote its vision of a better future for Indigenous Australians. He’s visited communities big and small, often with the Uluru Statement canvas rolled up in a tube under his arm. Here, through the story of his own journey and interviews with twenty key people, Mayor taps into a deep sense of our shared humanity. He believes that we will only find the heart of our nation when Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are recognised with a representative Voice enshrined in the Australian Constitution.

Too Much Lip by Melissa Lucashenko

Wise-cracking Kerry Salter has spent a lifetime avoiding two things - her hometown and prison. But now her Pop is dying and she’s an inch away from the lockup, so she heads south on a stolen Harley. Kerry plans to spend twenty-four hours, tops, over the border. She quickly discovers, though, that Bundjalung country has a funny way of grabbing on to people. And the unexpected arrival on the scene of a good-looking dugai fella intent on loving her up only adds more trouble - but then trouble is Kerry’s middle name. Gritty and darkly hilarious, Too Much Lip offers redemption and forgiveness where none seems possible.

Growing Up Aboriginal in Australia edited by Anita Heiss

What is it like to grow up Aboriginal in Australia? This anthology, compiled by award-winning author Anita Heiss, attempts to showcase as many diverse voices, experiences and stories as possible in order to answer that question. Accounts from well-known authors and high-profile identities sit alongside newly discovered voices of all ages, with experiences spanning coastal and desert regions, cities and remote communities. All of them speak to the heart - sometimes calling for empathy, oftentimes challenging stereotypes, always demanding respect.

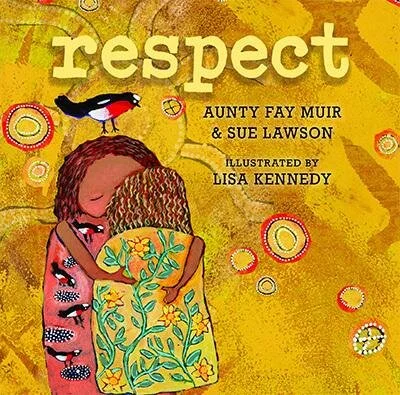

Respect by Aunty Fay Muir, Sue Lawson and Lisa Kennedy (illus.)

This tender and thoughtful picture book is the first in a new series, Our Place, which welcomes and introduces children to important elements of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander culture. Using spare and poetic text, a young girl is encouraged to respect culture, stories, song, ancestors, Elders, and Country. Authors Aunty Fay Muir and Sue Lawson have previously collaborated on the excellent language book Nganga, and you may know illustrator Lisa Kennedy from her work on Welcome to Country and Wilam: A Birrarung Story. The gorgeous language, universal themes and vibrant illustrations make Respect a truly beautiful book to pore over with little people.

Homeland Calling edited by Ellen van Neerven

Homeland Calling is a collection of poems created from hip-hop song lyrics that channel culture and challenge stereotypes. Written by First Nations youth from communities all around Australia, the powerful words display a maturity beyond their years. Edited by award-winning author and poet Ellen van Neerven, and brought to you by Desert Pea Media, the verses in this book are the result of young artists exploring their place in the world, expressing the future they want for themselves and their communities.

Australia Day by Stan Grant

As uncomfortable as it is, we need to reckon with our history. On January 26, no Australian can really look away. There are the hard questions we ask of ourselves on Australia Day. Since publishing his critically acclaimed, Walkley Award-winning, bestselling memoir Talking to My Country in early 2016, Stan Grant has been crossing the country, talking to huge crowds everywhere about how racism is at the heart of our history and the Australian dream. But Stan knows this is not where the story ends.

Welcome to Country: A Travel Guide to Indigenous Australia by Marcia Langton

Welcome to Country is a curated guidebook to Indigenous Australia and the Torres Strait Islands. Author Professor Marcia Langton offers fascinating insights into Indigenous languages and customs, history, native title, art and dance, storytelling, and cultural awareness and etiquette for visitors.

Black Politics by Sarah Maddison

Author Sarah Maddison interviewed a number or prominent activists, politicians and Aboriginal leaders including Mick Dodson, Tom Calma, Alison Anderson and Jackie Huggins, in an effort to put together a text that explores the dynamics of Aboriginal politics. If you’re looking to familiarise yourself with the numerous challenges faced by Indigenous communities, this book is a must.

Born Again Blakfella by Jack Charles, with Namila Benson

Born Again Blakfella, written by Jack Charles with the help of Namila Benson, chronicles the life of the musician and Senior Victorian Australian of the Year, who was stolen from his mother when he was merely a few months old. Often referred to as Uncle Jack Charles, the Aboriginal Elder shares his story in his eye-opening new autobiography.

Jacob's Well: The Circular

Last week, Br Ernesto Sanchez, the Superior-General of the Marist Brothers, released his first Circular, “Homes of Light.” It is number 420 in the history of these unique documents. You can find it here: https://champagnat.org/en/brother-ernesto-sanchez-presents-Circular-420-of-the-marist-institute/. Its release inspired me to answer the questions, what is a Circular, and what are they about?

The Circular is a type of message to a group of people. They are situated in a tradition going back to Saint Marcellin Champagnat, whose first Circular was composed in 1828. Since then, in the style proper to each person and each period, we find them, in thousands of pages, with news about family, information, instructions, recommendations, reflections on our life and mission. The other unique element about them are they are written by a Superior-General: it is a tradition reserved for this position, although a number of them had some help, and traditions are always malleable!

As mentioned, we have over four hundred of these messages, but they vary in length, content, context and style. Each Superior-General has put their own flavour in their Circulars or used them for specific purposes. In addition, they are changed over time, as technology and contexts has amended their purposes. For Champagnat, getting a message to the Brothers with specific instructions and practical news was his major concern, as sending letters in the post was the most effective means of mass communication. In more recent years, the Superiors-General have shifted to more philosophical and reflective ground. The Circulars have been more focussed on setting and communicating vision, reflecting on history, theology and the mission as key themes. Again, others have focussed on a specific topic, setting the tone for detailed action, as Br Benito Arbués, the eleventh Superior-General did in his Circular, “Concerning Our Material Goods.”

To give you a glimpse of their depth and breadth, here are some of the Circulars that continue to inform our Institute:

One of the first Circulars from Marcellin was short, concise and still full of richness. The Circulars started as short letters to the brothers. Here is an example:

Marcellin Champagnat

1830-08-15

This letter was no doubt a Circular intended for all the communities. The original, in fact, shows traces of another letter which was placed on top of it before the ink had dried. From these traces we can see that the other letter, at least in its opening lines, was identical with this one. We can therefore conclude that in the beginning Fr. Champagnat himself wrote out copies of his Circular letters to the eighteen communities which then made up the Institute, except perhaps for those he was going to visit within the next few days, to whom he would deliver the message in person.

As for the vacations, after the community moved down to the Hermitage, they had been and still were two months long, as before (Avit, AA, p. 98). We also know that the schools reopened around All Saints, so the vacation normally began in early September. Given the disturbances taking place in the country at that time, why was it thought better to delay the start of the vacation by two weeks? We have no way of knowing for sure. To get some idea of the climate of French society at this time, see the Introduction, above, and also Life, pp. 174-176; Avit, AA, pp. 96-98; O.M., I, pp. 481-482.

Jesus, Mary, St. Joseph

My dear friends,

I’m afraid I didn’t inform you that the vacation would begin only on 15th September. All the parish priests want it this way, and they say that the glory of God is involved here.

Don’t be frightened; Mary is our defender. The hairs of our head are all counted, and not one of them can fall without Gods permission. Let us be totally convinced that we have no greater enemy than ourselves. Only we can hurt ourselves; no one else can. God has said to the wicked, you can go just so far and no farther.

I leave you in the Sacred Hearts of Jesus and Mary. We do not forget you in our prayers. Pray for us, too.

I have the honour to be your very devoted father in Jesus and Mary,

Champagnat, sup. of the M.B.

Marys Hermitage, 5th August 1830

There have been many Circulars that reference or centre Mary, but this one marked one of the most challenging, renewing and visionary of Br Sean Sammon’s Circular. It offered a contemporary interpretation of the person of Mary, as well as invited the reader to take courageous action to move to new and confronting spaces. It also offered questions for reflection, marking a shift in style that invited personal and communal consideration. Check it out here: https://champagnat.org/en/Circulares/in-her-arms-or-in-her-heart/

Br Charles Howard, the only Australian Superior-General, was a man of tremendous presence and intellect. One of his great insights was the Circular “The Champagnat Movement of The Marist Family.” Written in 1991, the letter was ahead of its time: The Church, and many provinces of the Marist Institute, have been very slow to honour the longstanding vocational call and promise of the “laity.” This Circular outline many of the invitation and visions that we are only now still enacting and growing with our Marist Associations, and other movements of Marists around the world. It is also one of the first that explicitly addresses all members of the Marist family, not only the Brothers. Check it out here: https://champagnat.org/en/Circulares/the-champagnat-movement-of-the-marist-family/

Four down, four hundred and sixteen to go!

Jacob's Well: Marist Pilgrimages

In this third segment on pilgrimages, here are some examples of pilgrimages in our Marist story that are continuing to take shape. Although our short-term circumstances may limit the physical pursuits of these pilgrimages, the anticipation and preparation are just as important as the external movements towards them. They are all part of the journey.

Marcellin and his pilgrimages

The spiritual gifts of pilgrimages were instilled in Marcellin by his mother, Marie-Louise, from an early age. Although unable to travel great distances, pilgrimages to significant places of Christian history were popular throughout France in Marcellin’s time. One significant site for Marcellin and his family was La Louvesc. It is the site, of the Basilica of Saint John Francis Regis, a popular saint in France where his tomb is contained and is the site of significant religious history for the country. Currently, it also holds the incorrupt body of Saint Therese Couderc, founder of the Congregation of Our Lady of the Cenacle, and a contemporary of Marcellin.

One of the first recorded pilgrimages of Marcellin to this site came at the conclusion of one of the most difficult years of his initial education. At the end of one year, June-July, 1806, Father Perier, Superior of the seminary told him that he should not consider advanced studies. Saddened but not disheartened, Marcellin made a pilgrimage with his mother to La Louvesc, to the Tomb of Saint Regis, to implore Mary's help. During other times in his life, especially in times of difficult and seeking intercession, Marcellin would journey to this same holy place. In 1823, Br Jean-Baptiste Furet writes, “When the new troubles struck, Marcellin prescribed special prayers and called on the Community to fast for nine days on bread and water. He himself made a pilgrimage to the tomb of Saint John Francis Regis at La Louvesc, interceding with him for the necessary light and strength.” According to the testimony of Madame Sériziat on Father Champagnat's pilgrimages to La Louvesc, "The good Father Champagnat went rather often on pilgrimage to La Louvesc, on foot through the mountains. On his return, which was at night, he knelt on the door-steps outside the exterior church door and, bareheaded, remained in adoration of the Blessed Sacrament, awaiting in this manner, the opening of the church in order to be able to celebrate Holy Mass."

For Marcellin, a pilgrimage came at a time of great need and questioning. To journey with questions, doubts, and to ask for help are vital part of the pilgrim’s experience.

L’hermitage: the heart of Marist pilgrimages

The historical and spiritual home of the Marist Brothers, and those who follow in Champagnat’s footsteps, has always been L’Hermitage, located near the town of St-Chamond, in France. Built by Marcellin Champagnat and his first Brothers, the Brothers first moved from La Valla to the Hermitage in 1824. In 2010, the renovated Hermitage was inaugurated as a centre for Marist pilgrimage. The community welcomes and accompanies mainly Marist groups from around the world and local parish groups. It is an international community of Brothers and Laypeople, living under the same roof, sharing in a fraternal life, praying together and being co-responsible for their ministry to pilgrims. It is a special and beautiful place.

You can check out a virtual pilgrimage to Marcellin’s bedroom in the L’Hermitage, as well as the Chapel, constructed for the Feast Day of Champagnat this year: https://champagnat.org/en/dia-de-sao-marcelino-champagnat-peregrinacao-virtual/

LaValla and surroundings places

LaValla is more than a name for a building or a magazine. It is often referenced because the village, and a number of surrounding places and villages, are part of the fertile ground that gave life to the early Marist story. LaValla, Marcellin’s first parish, as well as Le Rosey, Marhles, Les Maisonettes, Le Bessat, and a number of other villages, are important sites of thousands of Marist pilgrims for decades. Being able to tread the streets where Marcellin walked is akin to travelling back in time. Walking through the harsh inclines and terrain of the mountains and hills of this area gives new insight into the conditions that led to the Memorare in the Snow story. Wadding in the cool waters of the River Gier as it cascades through the valley and refreshes the fields of L’Hermitage gives added weight to the imagery and spirituality of “Water from the Rock.” It is special country. It can be home. It can provide answers and refreshments, as well as challenges and questions. It calls you. Can you hear it?

Fourvière

Another important place of pilgrimage for Marists, across all branches of the greater Marist family, is the Marian shrine at Fourvière dedicated to Our Lady since 1170. Fourvière is an ancient site, now part of the Historic Site of Lyons World Heritage Site declared by UNESCO in 1998. Fourvière Hill was originally the location of the Roman Forum and a temple. As early as 1168, a Christian chapel was built on the hill, which by that time had already become a Marian shrine. The chapel was dedicated to the Virgin Mary and to the medieval English Saint Thomas Becket (1118-70). Its popularity as a place of pilgrimage increased significantly after Lyon’s preservation from plague in 1643 was interpreted as an answer to the prayers of the city leaders.

The interior of the chapel, restored in 1751, has not greatly changed since this time. The Basilica was consecrated in 1896, in fulfilment of a vow by the city of Lyon, and in thanksgiving to Our Lady for protecting the city from the ravages of the Franco-Prussian War of 1870, and Fourvière has always been a popular place of pilgrimage, as can be seen from the plaques placed round the wall of the chapel.

On 23rd July 1816 the twelve Marist aspirants, priests and seminarians, climbed the hill to the shrine of Our Lady of Fourvière. They placed their promise to found the Society of Mary under the corporal on the altar while Fr Jean-Claude Courveille celebrated Mass. After communion which they all received from Fr Courveille’s hand, they read out their declaration promising to devote themselves and all that they had to the foundation of the Society of Mary. On the left of the chancel is a plaque commemorating this event, and on the opposite side of the plaque commemorating the Marist Brothers (FMS). Since these early times many Marist celebrations have taken place either in this chapel or in the basilica but the first time that the four branches of the Marist Family celebrated together at Fourvière was on the 150th anniversary of the Fourvière pledge, 24 July 1966.

I hope this gives you all a taste of the concept and reality of pilgrimage in our Christian tradition. May you be inspired to continue to listen to God’s gently whisper, to pack a bag, and take those needed steps towards your personal invitations of freedom, growth and adventure.

Jacob's Well: Christian Places of Pilgrimage

The Christian sense of pilgrimage has a long history, though it is never explicitly explained in detail as a religious practice in the scriptures. Pilgrimage seems to mark its recorded beginnings as part of the Catholic tradition in the fourth century, when Christians wanted to travel to the places that were part of Jesus’ life, or to the graves of the martyrs and Saints Peter and Paul in Rome. As mentioned previously, pilgrimage is not a uniquely Christian practice, but its longevity and significance has added depth to one’s discipleship. A few pilgrimage trails, most notably Europe’s medieval Camino de Santiago, have been reconstituted in recent decades and become popular with Christians and non-Christians alike.

Pilgrimage is both a social and an interior process, and occurs both in individual or small group contexts, such as hiking the Camino de Santiago, and in organized group contexts, as with the tour groups that travel to Rome, Lourdes and Fatima. As was true in the Middle Ages, many people who travel on pilgrimages carry symbols like a scallop shell or a special scarf that mark them as pilgrims. These listed pilgrimages marks some of the more well-known and established routes of Christian history.

Pilgrimages to Jerusalem and the Holy Land

To a Christian, Jerusalem during the Middle Ages (500–1500) was a place of hope and desire. As a place of desire, Christians wanted to visit and experience the tactile as a way of deepening one’s relationship with Jesus by walking in the streets and churches that marked important locations in his life. As a place of hope, Jerusalem and other sites in the Holy Land set the heart on fire, because these sites were the origins of their faith. To be close to these places meant to be close to Jesus. This idea remains as true for Christians today, as it did hundreds of years ago.

The goal of any Christian living at that time was to make a pilgrimage to the Holy Land. At the time of the Crusades, the tradition of making such a trip to a sacred place already had a long history, dating back to the 300s and even earlier. The journey was difficult, long and treacherous: modes of transport, communication and provisions were very different to the comforts and ease of today’s tools of travel. Months of hard work, through culturally and linguistically diverse lands add personal and spiritual significance and hardship to the pilgrimage. The reward: Christians wanted to see the buildings that the Roman emperor Constantine had erected to house the holy sites during his reign in the fourth century. The flow of pilgrims slowed with the Muslim conquest of Jerusalem in the seventh century. Also, continuing political turmoil in Europe up through the ninth century made pilgrimages to the Holy Land the privilege of a select few.

By the twelfth century, travel to the Holy Land from Christian Europe was virtually impossible. The desire, however, remains as constant and palpable as ever, and people have continued their attempts to journey to Jerusalem and the Holy Land until the present day.

The Pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostela

One of the oldest pilgrimage routes in the world runs through Northern Spain, terminating at the cathedral of Santiago de Compostela. This is the burial site of St. James, whose remains were transported from Jerusalem to Spain by boat. For the average European in the twelfth Century, a pilgrimage to the Holy Land of Jerusalem was out of the question—travel to the Middle East was too far, too dangerous and too expensive. Santiago de Compostela in Spain offered a much more convenient option. Pilgrimages to the area haven’t ceased since medieval times, and the route has enjoyed revived popularity since the 1980s. The Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela now stands on this site.

Traveling pilgrims can expect barebones accommodations along the Camino de Santiago, or Way of St. James. Monasteries provide hostels for travellers and ask for small monetary donations in return. Pilgrims should be aware that a special Credencial, or religious passport, is required to stay at a monastic hostel.

The pious of the Middle Ages wanted to pay homage to holy relics, and pilgrimage churches sprang up along the route to Spain. Pilgrims commonly walked barefoot and wore a scalloped shell, the symbol of Saint James (the shell’s grooves symbolize the many roads of the pilgrimage). Along each part of the journey rests historical sites, churches and traditions that makes this pilgrimage one of the culturally and spiritually richest experiences, for Christians and non-Christians.

In France alone there were four main routes toward Spain. Le Puy, Arles, Paris and Vézelay are the cities on these roads and each contains a church that was an important pilgrimage site in its own right. Check out videos on the world’s largest thurible that swings throughout the Cathedral on special days and upon request (that request being a substantial donation!): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xndYdKR5tY0

Via Francigena: The Pilgrimage to Rome

From Breena Kerr (http://www.bbc.com/travel/story/20181203-a-1000-year-old-road-lost-to-time):

In 990AD, the Archbishop of Canterbury named Sigeric the Serious had a more practical reason to walk to Rome. Having risen into his prestigious office, he needed to visit the Vatican to be ordained and collect his official garments. At the time he made the journey, there were many different paths to Rome. But Sigeric, who’d left from Canterbury, wrote down his route home through Italy, Switzerland, France and into the UK, cataloguing the towns he stayed in on his journey. The route he took now makes up the official Via Francigena. The only part that cannot be completed on foot is the English Channel, which medieval pilgrims crossed by boat (and modern pilgrims on the Dover-to-Calais ferry).

As the Renaissance blossomed in Europe, the Via Francigena began to decline in popularity. Trading routes multiplied and shifted to pass through Florence, one of Italy’s most significant intellectual, artistic and mercantile cities at the time. As the Romans expanded their dominion, they built roads to connect the conquered cities back to heart of the empire.

The Via Francigena became, for the most part, forgotten, although sections remained in use as local roads and footpaths. Things remained that way until 1985. That year, a Tuscan anthropologist, writer and adventurer named Giovanni Caselli was looking for new topics to write travel books about. As an enthusiastic hiker who had also walked the old Silk Road through China, Uzbekistan and Tajikistan, Caselli decided to walk the Via Francigena after learning about Sigeric’s route.

“I would go into a town and ask the local people, ‘What’s the oldest route from here to there’,” he said. “And it worked, because the local memory of these paths still exists.” Caselli walked all the way from Canterbury to Rome, crossing the British countryside, the English Channel (by ferry), French Champagne country, the Swiss Alps and the rolling hills of Tuscany.

After Caselli published his book about the Via Francigena in 1990, the route started gaining attention. In 1994, the Via Francigena became one of the Council of Europe’s designated Cultural Routes. Then in 2006, the organisations that oversee the Via Francigena decided on the official route that pilgrims walk today. Many pilgrims see it as an alternative or follow-up to Spain’s better known – and much busier – Camino de Santiago.

Marian Shrines: Places of Miracles

Tied to the history of Christian pilgrimages resides Mary. All over the world, pilgrimages to places with stories, devotions and encounters with Mary, the Mother of Jesus, exist on almost every continent (a Marian shrine at Antarctica is yet to be established: maybe Mary doesn’t like the cold?). Ranging from the well-known places of Lourdes and Fatima, to smaller shrines in most obscures locations in Yankalilla, South Australia, Penrose Park, New South Wales and Canungra, Queensland, the journeying to these Marian places is another benchmark of Christianity pilgrimages.

There are some many more places of pilgrimage to list, both here in Australia and overseas. Hopefully we will be able to visit them one day! What are some of your favourites?

And as a preview for next week, we will look at important Marist places of pilgrimages and the places where Marcellin went on pilgrimage too!

Jacob's Well: Pilgrimage

Another request has arrived. I was asked to share on some of my overseas experiences, and boy, was I excited! I love to share my travel stories, but upon reflection, realise that the same enthusiasm may not exist for other people! For me, I have struggled through hours of photos of relatives and their overseas trips, and I am forever traumatised. Instead, I thought I would share these stories with the underlying sense of their purpose, for me: to go on pilgrimage. In the coming weeks, I want to share some major places of pilgrimage within the Christian tradition, as well places of Marist pilgrimage. Firstly, however, let’s explore together the foundations of pilgrimage.

The act of making a pilgrimage – traveling to a sacred place to encounter the divine – is ancient, probably as old as humanity itself. Its spiritual significance exists in every major religions and faith system. The people of God, descended from Abraham, experienced their seminal formative journey from Egypt to the Promised Land in such a powerful way that it shaped their entire religious, cultural and personal identities.

Pilgrimages are undertaken for many reasons: seeking healing and peace, an attempt to make amends, to do penance, to seek answers to questions, to lose weight or to visit a sacred site. Often, it is thought that the destination is the focus of the journey, and that the way of getting from point A to point B is simply the practical manifestation of getting to this arrival. However, a pilgrim realizes that the journey is essential to the pilgrimage. The journey teaches us about ourselves. Why am I short-tempered with my fellow travellers? Do I dread the details of the journey? What am I feeling on the journey? In addition, the journey allows us to be drawn into a deeper relationship with God. How do I encounter the holy on this quest? What is God inviting me to learn, not only at our destination, but on the way? How is God present with me on the journey?

As Christians, we are a pilgrim people. We are always journeying to the most sacred of places. For some, this is expressed journeying to heaven, or building the Kingdom of God or to holy ground. This sacred place is more aptly described as experiencing the fullness of God coupled with the sense of returning home. This is the invitation and gift of pilgrimage: a journey of growing into fullness, and recognising God is present at all stages. In order to make the most of this journey, we must plan well. We need to be fed: Scripture and the Eucharist will provide some of the sustenance needed. A journey requires a map: the guidance that prayer gives us. We travel with others (family, friends, co-workers, strangers) and we are invited to discern the places and reasons that each of these people are present in our life, into our pilgrimage, for God does nothing by chance.

Pilgrimage is a pervasive theme throughout Scripture. The Apostle Peter refers to it often, and at the beginning of his first epistle, he addresses believers as sojourners and pilgrims (1 Peter 2:11). Similarly, the Apostle Paul constantly reminds us of our pilgrim status when informing us that our citizenship is in heaven: For our citizenship is in heaven, from which we also eagerly wait for the Saviour, the Lord Jesus Christ (Philippians 3:20). The letter to the Hebrews is an operating manual for the Christian’s pilgrimage. It locates the Christian squarely in the desert, likening the Christian life to the wilderness wanderings in the Old Testament. The Old Testament is full of references, understandings and experiences of pilgrimages. Our Christian understanding of pilgrimage is deeply informed by our Jewish ancestors.

The invitation of being on pilgrimage is more than a physical one. In our current circumstances, we are limited in being able to access, or not access, the traditional geographical places of pilgrimages. However, we are never limited to take on the perspective and heart of a pilgrim.

There is a richness of literature that exists on pilgrimage, especially in the Christian tradition. Please explore it: I will add some more over the coming weeks. I offer a couple of introductory reflections on pilgrimage that may assist you in moving into a pilgrim’s mindset.

From Dee Dyas, The University of York:

The Old Testament presents several physical journeys which also have a deeper spiritual meaning. The journey made by Abraham and the story of the Exodus from Egypt both emphasise the theme of God journeying with his people and stress the importance of being willing to obey and trust God. Abraham, a key figure in Judaism, Christianity and Islam, is shown in Genesis 12:1-9 leaving his home to go in search of a land which God promises to show him, becoming a 'pilgrim' or 'sojourner' whose willingness to obey God makes him a model of faith and obedience. In the story of the Exodus from Egypt, the Israelites travel through the wilderness to the land of Canaan, experiencing both hardships and God's care and guidance. The Exodus motif plays a key role in Christian thought and the long journey through the wilderness towards the Promised Land was later interpreted as a paradigm or model of the Christian journey through a fallen world towards heaven.

In time, the city of Jerusalem developed into a centre of pilgrimage, a place where God could be encountered in a special way. Pilgrimage to Jerusalem on the three feasts of Passover, Weeks and Booths became a requirement for all male Israelites who would often have been joined by other family members. During periods of exile, pilgrimage to Jerusalem took on additional emotional and spiritual significance.

The New Testament picks up many motifs from the Old Testament but also shows some important changes in emphasis. The Fall of Humankind, and the stories of alienation, disobedience and conflict which follow, provide the backdrop to the drama of redemption told in the New Testament. In the Gospels, Jesus Christ is shown winning forgiveness for humankind through his death on the Cross, making it possible for individuals to return to God and eventually reach heaven, vividly portrayed in the Book of Revelation (Revelation 21:9-22:5). The focus shifts from seeking God in the earthly city of Jerusalem to finding him in Jesus Christ, believed to be God made man.

New Testament writers stress that salvation will be offered for a limited time only before Jesus Christ returns to judge humankind (Matthew 25:31-33). This event, often called the Last Judgement, will be unexpected (Matthew 24:36-44) and cataclysmic (2 Peter 3:10-13), as the created world dissolves and is remade. Human beings therefore need to be aware of the essential transience of this world and its pleasures (John 2:17; 1 Corinthians 7:31; James 1:11) and prepare themselves to face God's verdict on the way they have lived. Christians are therefore encouraged to see themselves as 'pilgrims and strangers on the earth', 'temporary residents' whose true home is in heaven (1 Peter 2:11; Hebrews 11:13). The Christian life itself is thus seen as a journey towards that homeland in which the individual believer seeks to follow and obey Christ through an alien, frequently hostile world (John 14:6; Mark 8:34). Figures such as Abraham are presented as examples of faith to be imitated (Hebrews 11:1-16).

From Robert B. Kruschwitz, Baylor University.

Pilgrimage typically involves traveling to places that are closely associated—through art, architecture, or a saint’s life—with God’s mission in the world. In its essence, “pilgrimage is a journey nearer to the heart of God and deeper into life with God,” Eric Howell explains. “The hope of all pilgrimage is realized when we have renewed eyes to be happily surprised by God’s mysterious presence in all times and places, even at home.” After sketching the history of this practice, Christian George commends pilgrimage for Christians of all ages and abilities, “as a spiritual discipline that reflects our journey to God, that gives great energy to our sanctification, and that engenders a spiritual vitality that is both Christo-centric and community-driven.”

The history of Christian pilgrimage draws on biblical travels to the festivals at the Second Temple in Jerusalem (537 bc-ad 70). Peter describes all believers as pilgrims (1 Peter 2:11), for they join Abraham’s walk toward a city built by God. Christian George notes, “By the time Constantine’s mother, Empress Helena, brought pilgrimage into vogue by traveling to the Holy Land in 326, a living tradition of sancta loca, or holy places, pertaining to the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus Christ had already materialized.” Detractors from Gregory of Nyssa (c. 335-c. 395) to the Protestant Reformers criticized the physical dangers and spiritual excesses of pilgrimage, yet the practice flourished in the medieval period and revived in the eighteenth century. Great European cathedrals, sites of martyrdom, and places where notable saints had served were added to the list of destinations. Even the Puritans, who objected most to the corruptions of pilgrimage, nevertheless “embraced biblical precedents like Abraham’s journey, Israel’s Exodus, and the sacred travels of the Magi, giving great exegetical and homiletical attention to the pilgrim psalms 120-134, Christ’s infant journey to Egypt, and New Testament passages like these.”

Pilgrimage today “to places like Iona, Taizé, Skellig Michael, Mont St. Michelle, Mount Athos, Assisi, Jerusalem, and Rome…can serve as a unifying commonality among Christians of every denomination and tradition, [which] fosters reconciliation and ecumenism,” George notes. Anyone can practice the discipline of pilgrimage—children seeking to concretize their faith, young people hiking across Europe, or adults seeking spiritual renewal. “Those who cannot travel—the elderly, the poor, the hospitalized, or those with physical disabilities” practice pilgrimage by setting the Lord always before them. He explains, “some of the greatest pilgrimages I have ever taken have been in the midnight moments of my life, the hospital moments when I opened up the Bible and travelled to Jericho, where the walls came tumbling down.

As an armchair pilgrim, I went to Egypt and saw the Red Sea stand up for God’s people to march through.” “The discipline of pilgrimage reminds us to slow down and take life one step at a time. It reminds us that life is an emotional, physical, and spiritual journey that requires upward and inward conditioning. It moves us from certainty to dependency, from confidence to brokenness, from assurance in ourselves to faith in God,” George concludes. “A regular diet of spiritual disciplines like pilgrimage can splash our dehydrated Christianity with fresh faith and gives us a greater hunger for the holy.”

Check out the Metropolitan Museum of Art: Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History Essays: Pilgrimage in Medieval Europe: https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/pilg/hd_pilg.htm

For a musical sense of the purpose and emotional heart of the idea of pilgrimage, based on Psalm 23 and 1 Thessalonians 5: 16-17, have a listen to Paul Kelly and the Stormwater Boys, “Meet Me in the Middle of the Air.”

Buen Camino!

Jacob's Well: Subsidiarity

Continuing to draw on the richness of Catholic Social Teaching tradition, I wanted to share some thoughts on a lesser known, but equally important, concept of subsidiarity. It often gets lost in the workings and emphases of our Church, but it is crucial in building the Kingdom of God that is grounded in justice, fairness, respect for every person and in modelling power structures that are accessible, inclusive and revolutionary. It is often linked with the concept of participation as well, and this link is significant and broad. I will cover this in a future edition.

Firstly, the resources!

I love the resources from Caritas Australia on our Catholic Social Teaching:

https://www.caritas.org.au/learn/cst/subsidiarity-and-participation

PovertyCure is an initiative of the Acton Institute that seeks to ground the battle against local and global poverty in a proper understanding of the human person and society, and to encourage solutions that foster opportunity and unleash the entrepreneurial spirit that already fills poverty-stricken areas of the developed and developing world.

https://www.povertycure.org/learn/issues/human-person/subsidiarity

Secondly, I wanted to share some thoughts (some of the best I have ever experienced) from one of my favourite lecturers and teachers while I was in the Philippines, Francisco Castro. Here are some of his thoughts on subsidiarity that really explain and engage the concept.

In the early centuries of most of our countries, people were grouped in small units. There was still no such thing as big nations with centralized states. Political power, which was in a very minimum, was mostly involved with making sure there was peace and order among people. The different groups and individuals were made to unify peacefully, more or less. So what we would find, at that time, was the dominance of small social units like the family and the village.

2. Slowly, over time, societies became more complex…and slowly centralized States were organized. In passing, it may be interesting look at the history of the Church. What we can notice is that the Church played a social role that later will be done by the State. Affairs like education and health care were more in the hands of Church activities than in the States. If one had any problems, it was mainly the Church who was consulted. Even Kings and Princes consulted the Church.

3. Later on, societies became really complex and the State became more important. Then began the problem of State rule and domination. Some philosophers and even theologians began to promote the idea of freedom in front of centralized State authorities. So there was the beginning of moving out of the “organic” living in society to a more individual living in society. Surely we see the effects even today.

4. Over the course of history more and more societies tried to look for autonomy of local groups. More and more the government was understood as “helping out” the local levels. The totalitarian way was discouraged. Taking care of the whole society should not be the exclusive competence of the State. People, in individual and small units, had to have a voice. This was the start of “subsidiarity”.

5. So this idea of subsidiarity is not anything new in history. During the time of Pope Leo XIII the big problem was industrialisation—many people were in very hard work conditions. Many individuals and families did not have a voice in their work conditions. So Catholics called for help—how to help the voiceless workers of industrialism.

6. Years later, with the “Cold War”, the human rights were so violated by governments. Pope John XXIII for example, had to worry about how to limit the power of States over individuals. He raised the question of how to let everyone have a voice in governance of whole societies.

7. Society is basically composed of people. This is easy to see. But how are people living together—socially? The Compendium gives us an idea of this “living together” by discussing civil society (see Compendium #185). Civil society involves all and everyone in society related as individuals and as groups. Individuals are not isolated from one another. Individuals are social beings—they live “in” a social setting. Each individual is really within a network of relationships with others.

8. As each individual (and we can also add the small social group like the family) lives within a wider social setting, each one can take an initiative regarding how to live and how to pursue happiness. It is not wise to remove this capacity to take initiative. Every social activity must keep in mind the place that each one can have—the role that each one can play for the good of the whole. In society we find more complex and more assembled areas…but we also find individuals. We find the “higher orders” and also the “lower orders”. An example of a higher order is “the economic world” or “the market” or “the State”. An example of the “lower order” is me and my family, me and my circle of friends, or even myself. Social life is not just run by the “higher orders” …it is also run by the “lower orders”.

9. Compendium 186 would insist that a society must have the “attitude of subsidiarity”. This is the attitude of supporting, promoting and developing the “lower orders” of society. Let this not look so abstract. What the document is saying is that people—even in their own levels of social life—must have the chance to say something about the way the whole society should run. Let people—individuals and small social units—have a role. Let people in the “lower level” have a voice.

10. Why is this important? This is important because very often in society the small individual level—the “lower level”—is “absorbed and substituted”. Only the higher order makes decisions. Only the higher order says how society should run…and everyone else just follows. The individual, therefore, is so absorbed in the group and it is the group that substitutes for the individual.

11. So we read that subsidiarity is a way of “assistance offered to lesser social entities” (186). Now because the lower order is respected, the higher order—like the State—should “refrain from anything that would de facto restrict the existential space of the smaller essential cells of society” (186). The initiative, freedom and responsibility of social members in their own realms must not be supplanted.

12. Is this important? Yes, it is. If individuals and very small social units have no voice, they can be easily abused by the higher levels. It is also important because t reminds the higher orders to give space for the lower orders. Again, as we said above, give voice to the people. “This principle is imperative because every person, family and intermediate group has something original to offer to the community” (187). The absence of subsidiarity would result to the ruin of initiative and freedom. There will be the domination of bureaucracy, for example. There will be the domination of big monopolies of higher levels.

13. So how will subsidiarity be put to effect? The Compendium proposes the following (187):

· “respect and effective promotion of the human person and the family;

· ever greater appreciation of associations and intermediate organizations in their fundamental choices and in those that cannot be delegated to or exercised by others;

· the encouragement of private initiative so that every social entity remains at the service of the common good, each with its own distinctive characteristics;

· the presence of pluralism in society and due representation of its vital components;

· safeguarding human rights and the rights of minorities;

· bringing about bureaucratic and administrative decentralization;

· striking a balance between the public and private spheres, with the resulting recognition of the social function of the private sphere;

· appropriate methods for making citizens more responsible in actively “being a part” of the political and social reality of their country”.

14. Be careful. The document is not saying that the higher order be dropped. The higher order must be present and active. But it should always stimulate the lower order. For example, there is the need to “stimulate the economy because it is impossible for civil society to support initiatives on its own” (187). Once the lower order is stimulated and given the chance to take initiatives, then the higher level will again have to refrain from intervening. The Compendium tells us that “institutional substitution must not continue any longer than is absolutely necessary, since justification for such intervention is found only in the exceptional nature of the situation” (187).

Finally, I wanted to share again some glimpses of some of the wisdom of the Church that engage and explain the concept of subsidiarity in a concise manner.

Still, that most weighty principle, which cannot be set aside or changed, remains fixed and unshaken in social philosophy: Just as it is gravely wrong to take from individuals what they can accomplish by their own initiative and industry and give it to the community, so also it is an injustice and at the same time a grave evil and disturbance of right order to assign to a greater and higher association what lesser and subordinate organizations can do. For every social activity ought of its very nature to furnish help to the members of the body social, and never destroy and absorb them.

Quadragesimo Anno (“After Forty Years”), Pope Pius XI, 1931, #79.

State and public ownership of property is very much on the increase today. This is explained by the exigencies of the common good, which demand that public authority broaden its sphere of activity. But here, too, the “principle of subsidiary function” must be observed. The State and other agencies of public law must not extend their ownership beyond what is clearly required by considerations of the common good properly understood, and even then there must be safeguards. Otherwise private ownership could be reduced beyond measure, or, even worse, completely destroyed.

Mater et Magistra (“Mother and Teacher”), Pope John XXIII, 1961, #117.

Private enterprise too must contribute to an economic and social balance in the different areas of the same political community. Indeed, in accordance with “the principle of subsidiary function,” public authority must encourage and assist private enterprise, entrusting to it, wherever possible, the continuation of economic development.

Mater et Magistra (“Mother and Teacher”), Pope John XXIII, 1961, #152.

The same principle of subsidiarity which governs the relations between public authorities and individuals, families and intermediate societies in a single State, must also apply to the relations between the public authority of the world community and the public authorities of each political community. The special function of this universal authority must be to evaluate and find a solution to economic, social, political and cultural problems which affect the universal common good. These are problems which, because of their extreme gravity, vastness and urgency, must be considered too difficult for the rulers of individual States to solve with any degree of success.

Pacem in Terris (“Peace on Earth”), Pope John XXIII, 1963, #140.

It is for the international community to coordinate and stimulate development, but in such a way as to distribute with the maximum fairness and efficiency the resources set aside for this purpose It is also its task to organize economic affairs on a world scale, without transgressing the principle of subsidiarity, so that business will be conducted according to the norms of justice. Organizations should be set up to promote and regulate international commerce, especially with less developed nations, in order to compensate for losses resulting from excessive inequality of power between nations. This kind of organization accompanied by technical, cultural, and financial aid, should provide developing nations with all that is necessary for them to achieve adequate economic success.

Gaudium et Spes (“The Church in the Modern World”), Vatican II, 1965, #86(c).

The primary norm for determining the scope and limits of governmental intervention is the “principle of subsidiarity” cited above. This principle states that, in order to protect basic justice, government should undertake only those initiatives which exceed the capacities of individuals or private groups acting independently. Government should not replace or destroy smaller communities and individual initiative. Rather it should help them contribute more effectively to social well-being and supplement their activity when the demands of justice exceed their capacities. This does not mean, however, that the government that governs least, governs best. Rather it defines good government intervention as that which truly “helps” other social groups contribute to the common good by directing, urging, restraining, and regulating economic activity as “the occasion requires and necessity demands”.

Economic Justice for All, U.S. Catholic Bishops, 1986, #124.

The “principle of subsidiarity” must be respected: “A community of a higher order should not interfere with the life of a community of a lower order, taking over its functions.” In case of need it should, rather, support the smaller community and help to coordinate its activity with activities in the rest of society for the sake of the common good.

Centesimus Annus (“The Hundredth Year,” Donders translation), Pope John Paul II, 1991, #48.

It is true that the pursuit of justice must be a fundamental norm of the State and that the aim of a just social order is to guarantee to each person, according to the principle of subsidiarity, his share of the community’s goods. This has always been emphasized by Christian teaching on the State and by the Church’s social doctrine.

Deus Caritas Est (“God is Love”), Pope Benedict XVI, 2005, #26.

Love—caritas—will always prove necessary, even in the most just society. There is no ordering of the State so just that it can eliminate the need for a service of love. Whoever wants to eliminate love is preparing to eliminate man as such. There will always be suffering which cries out for consolation and help. There will always be loneliness. There will always be situations of material need where help in the form of concrete love of neighbour is indispensable.[20] The State which would provide everything, absorbing everything into itself, would ultimately become a mere bureaucracy incapable of guaranteeing the very thing which the suffering person—every person—needs: namely, loving personal concern. We do not need a State which regulates and controls everything, but a State which, in accordance with the principle of subsidiarity, generously acknowledges and supports initiatives arising from the different social forces and combines spontaneity with closeness to those in need. The Church is one of those living forces: she is alive with the love enkindled by the Spirit of Christ. This love does not simply offer people material help, but refreshment and care for their souls, something which often is even more necessary than material support. In the end, the claim that just social structures would make works of charity superfluous masks a materialist conception of man: the mistaken notion that man can live “by bread alone” (Mt 4:4; cf. Dt 8:3)—a conviction that demeans man and ultimately disregards all that is specifically human.

Deus Caritas Est (“God is Love”), Pope Benedict XVI, 2005, #28b.

The strengthening of different types of businesses, especially those capable of viewing profit as a means for achieving the goal of a more humane market and society, must also be pursued in those countries that are excluded or marginalized from the influential circles of the global economy. In these countries it is very important to move ahead with projects based on subsidiarity, suitably planned and managed, aimed at affirming rights yet also providing for the assumption of corresponding responsibilities. In development programmes, the principle of the centrality of the human person, as the subject primarily responsible for development, must be preserved. The principal concern must be to improve the actual living conditions of the people in a given region, thus enabling them to carry out those duties which their poverty does not presently allow them to fulfil. Social concern must never be an abstract attitude. Development programmes, if they are to be adapted to individual situations, need to be flexible; and the people who benefit from them ought to be directly involved in their planning and implementation.

Caritas in Veritate (“Charity in Truth”), Pope Benedict XVI, 2009, #47.

A particular manifestation of charity and a guiding criterion for fraternal cooperation between believers and non-believers is undoubtedly the principle of subsidiarity, an expression of inalienable human freedom. Subsidiarity is first and foremost a form of assistance to the human person via the autonomy of intermediate bodies. Such Underlying the principle of the common good is respect for the human person as such, endowed with basic and inalienable rights ordered to his or her integral development. It has also to do with the overall welfare of society and the development of a variety of intermediate groups, applying the principle of subsidiarity. Outstanding among those groups is the family, as the basic cell of society. Finally, the common good calls for social peace, the stability and security provided by a certain order which cannot be achieved without particular concern for distributive justice; whenever this is violated, violence always ensues. Society as a whole, and the state in particular, are obliged to defend and promote the common good.

Laudato Si’ (“Praise Be”), Pope Francis, 2015, Chapter 4, #157.

[T]he principle of subsidiarity is particularly well-suited to managing globalization and directing it towards authentic human development. In order not to produce a dangerous universal power of a tyrannical nature, the governance of globalization must be marked by subsidiarity, articulated into several layers and involving different levels that can work together. Globalization certainly requires authority, insofar as it poses the problem of a global common good that needs to be pursued. This authority, however, must be organized in a subsidiary and stratified way[138], if it is not to infringe upon freedom and if it is to yield effective results in practice.

Caritas in Veritate (“Charity in Truth”), Pope Benedict XVI, 2009, #57-58.

The principle of subsidiarity must remain closely linked to the principle of solidarity and vice versa, since the former without the latter gives way to social privatism, while the latter without the former gives way to paternalist social assistance that is demeaning to those in need.

Caritas in Veritate (“Charity in Truth”), Pope Benedict XVI, 2009, #57-58.

It is the responsibility of the State to safeguard and promote the common good of society.[188] Based on the principles of subsidiarity and solidarity, and fully committed to political dialogue and consensus building, it plays a fundamental role, one which cannot be delegated, in working for the integral development of all. This role, at present, calls for profound social humility.

Evangelii Gaudium (“Joy of the Gospel”), Pope Francis, 2013, Chapter 4, #240

Let us keep in mind the principle of subsidiarity, which grants freedom to develop the capabilities present at every level of society, while also demanding a greater sense of responsibility for the common good from those who wield greater power.

Laudato Si’ (“Praise Be”), Pope Francis, 2015, Chapter 5, #196.

Jacob's Well: Solidarity

“If you want peace, work for justice.” Pope Paul VI’s invitation in the encyclical Populorum Progressio or “The Development of Peoples” in 1967 marks a significant articulation of one of the keystones of Catholic Social Teaching: Solidarity. The core of solidarity is this, ‘God asks us to look at our lifestyles and to live simply, sustainably and in solidarity with those in poverty.’

Catholic Social Teaching is often described as one of the hidden treasures of the Catholic Church. The tradition of solidarity has been intensively engaged with over the history of the Church, but the reforms and invitations of the Second Vatican Church propelled Catholic Social Thought into the forefronts of theology and education.

It is grounded in the evangelical invitation of Jesus in Matthew 25: In truth I tell you, in so far as you did this to one of the least of these brothers [or sisters] of mine, you did it to me. (Matthew 25:40)

I love the resources from Caritas Australia on our Catholic Social Teaching:

https://www.caritas.org.au/learn/cst/solidarity

Catholic Social Teaching.org.uk is a livesimply initiative, a network of 60+ charities who support the radical idea that God calls us to look hard at our lifestyles and live simply, sustainably and in solidarity with poor people at home and overseas:

http://www.catholicsocialteaching.org.uk/themes/solidarity/

Check out this fantastic article that explores solidarity in the context of Laudato Si.

https://www.americamagazine.org/issue/laudato-si-joins-tradition-catholic-social-teaching

CST 101 is a collaborative 7-part video and discussion guide series presented by the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops and Catholic Relief Services on Catholic social teaching. The videos bring the themes of Catholic social teaching to life and inspire us to put our faith into action.

https://www.crs.org/resource-center/CST-101?tab=solidarity

Finally, I wanted to share some glimpses of some of the wisdom of the Church that engages and explains the concept of solidarity in a concise manner. If you have made it this far (who knows who reads this!), thanks for being in solidarity with me as we journey into this important awareness!

Solidarity is not a feeling of vague compassion or shallow distress at the misfortunes of so many people, both near and far. On the contrary, it is a firm and persevering determination to commit oneself to the common good; that is to say to the good of all and of each individual, because we are all really responsible for all.

- Saint Pope John Paul II, On Social Concern [Sollicitudo rei Socialis], 38

It is a word that means much more than some acts of sporadic generosity. It is to think and to act in terms of community, of the priority of the life of all over the appropriation of goods by a few. It is also to fight against the structural causes of poverty, inequality, lack of work, land and housing, the denial of social and labour rights. It is to confront the destructive effects of the empire of money: forced displacements, painful emigrations, the traffic of persons, drugs, war, violence and all those realities that many of you suffer and that we are all called to transform. Solidarity, understood in its deepest sense, is a way of making history, and this is what the Popular Movements do.

- Pope Francis, World Meeting of Popular Movements 2014

To love someone is to desire that person's good and to take effective steps to secure it. Besides the good of the individual, there is the good that is linked to living in society: the common good. It is the good of "all of us", made up of individuals, families and intermediate groups who together constitute society. … To desire the common good and strive towards it is a requirement of justice and charity.

- Pope Benedict XVI, Charity in Truth [Caritas in Veritate], 7

It is good for people to realize that purchasing is always a moral — and not simply economic — act. Hence the consumer has a specific social responsibility, which goes hand-in- hand with the social responsibility of the enterprise. Consumers should be continually educated regarding their daily role, which can be exercised with respect for moral principles without diminishing the intrinsic economic rationality of the act of purchasing… It can be helpful to promote new ways of marketing products from deprived areas of the world, so as to guarantee their producers a decent return.

- Pope Benedict XVI, Charity in Truth [Caritas in Veritate], 66

At another level, the roots of the contradiction between the solemn affirmation of human rights and their tragic denial in practice lies in a notion of freedom which exalts the isolated individual in an absolute way, and gives no place to solidarity, to openness to others and service of them. . . It is precisely in this sense that Cain’s answer to the Lord's question: "Where is Abel your brother?" can be interpreted: "I do not know; am I my brother's keeper?" (Gen 4:9). Yes, every man is his "brother's keeper", because God entrusts us to one another.

- St. Pope John Paul II, The Gospel of Life [Evangelium Vitae], no. 19

Interdependence must be transformed into solidarity, based upon the principle that the goods of creation are meant for all. That which human industry produces through the processing of raw materials, with the contribution of work, must serve equally for the good of all.

- St. John Paul II, On Social Concern [Sollicitudo rei Socialis], 39

We have to move from our devotion to independence, through an understanding of interdependence, to a commitment to human solidarity. That challenge must find its realization in the kind of community we build among us. Love implies concern for all - especially the poor - and a continued search for those social and economic structures that permit everyone to share in a community that is a part of a redeemed creation (Rom 8:21-23).

- United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, Economic Justice for All, 365

The solidarity which binds all men together as members of a common family makes it impossible for wealthy nations to look with indifference upon the hunger, misery and poverty of other nations whose citizens are unable to enjoy even elementary human rights. The nations of the world are becoming more and more dependent on one another and it will not be possible to preserve a lasting peace so long as glaring economic and social imbalances persist.

St. Pope John XXIII, On Christianity and Social Progress [Mater et Magistra], 157

III. HUMAN SOLIDARITY (Catechism of the Catholic Church).

(Please note: excuse the outdated gendered language: this is the language of the Church at a specific time in history and has not been retranslated)

1939 The principle of solidarity, also articulated in terms of "friendship" or "social charity," is a direct demand of human and Christian brotherhood.

1940 Solidarity is manifested in the first place by the distribution of goods and remuneration for work. It also presupposes the effort for a more just social order where tensions are better able to be reduced and conflicts more readily settled by negotiation.

1941 Socio-economic problems can be resolved only with the help of all the forms of solidarity: solidarity of the poor among themselves, between rich and poor, of workers among themselves, between employers and employees in a business, solidarity among nations and peoples. International solidarity is a requirement of the moral order; world peace depends in part upon this.

1942 The virtue of solidarity goes beyond material goods. In spreading the spiritual goods of the faith, the Church has promoted, and often opened new paths for, the development of temporal goods as well. And so, throughout the centuries has the Lord's saying been verified: "Seek first his kingdom and his righteousness, and all these things shall be yours as well":

Jacob's Well: Mental Health

Our mental health and wellbeing are crucial parts of our overall health. We are growing, as a society, to talk more openly about our mental health. We are learning this truth more and more: it is ok not to be ok.

Here are some resources for your ongoing mental health, for your own use, or to offer as helpful resources to people in our ministries. A number of these services are offering COVID-19 specific services and programs. The online spaces offer privacy and security, while still providing comprehensive and personal service. A number of these sites offer connection to a health care professional if needed or wanted.

Please look after yourself, and please share your feelings and mental health with people in your life that you trust, love and find support. In addition, reach out for help whenever you need it. I am here to listen and be present, as well as other people in our team, in our Marist ministries and in professional mental health services .

Mindspot

MindSpot is a free service for Australian adults who are experiencing difficulties with anxiety, stress, depression and low mood. We provide assessment and treatment courses, or we can help you find local services that can help. The MindSpot team comprises experienced and AHPRA-registered mental health professionals including psychologists, clinical psychologists and psychiatrists who are passionate about providing a free and effective service to people all over Australia. We have a dedicated IT team to ensure that this happens as securely and efficiently as possible. MindSpot is based at Macquarie University, Sydney. We are funded by the Australian Government and contracted by the Department of Health as a regulated clinical service. We are Australia’s only free therapist-guided digital mental health clinic. We provide information about mental health, online assessments, and online treatment to adults with anxiety, stress, depression and chronic pain.

Beyond Blue

Beyond Blue provides information and support to help everyone in Australia achieve their best possible mental health, whatever their age and wherever they live. Beyond Blue is here to help people in Australia understand that these feelings can change. We want to equip them with the skills they need to look after their own mental health and wellbeing, and to create confidence in their ability to support those around them. Our vision is for everyone in Australia to achieve their best possible mental health. Through our support services, programs, research, advocacy and communication activities, we’re breaking down the stigma, prejudice and discrimination that act as barriers to people reaching out for support.

https://www.beyondblue.org.au/

Moodgym

Moodgym is like an interactive self-help book which helps you to learn and practise skills which can help to prevent and manage symptoms of depression and anxiety. It is like an interactive, online self-help book which teaches skills based on cognitive behaviour therapy. Moodgym consists of five interactive modules which are completed in order.

This Way Up

This Way Up is an online initiative of the Clinical Research Unit for Anxiety and Depression, UNSW at St. Vincent’s Hospital, Sydney. At This Way Up we believe that everyone should be able to access practical, effective, and evidence-based resources to help them improve their mental health. Our team of dedicated mental health clinicians have taken the research-backed tools and strategies used in face-to-face psychological treatment, and created practical online courses to guide you through using new coping skills to improve how you’re feeling.

headspace

headspace began in 2006 to address this critical gap, by providing tailored and holistic mental health support to 12 - 25 year olds. With a focus on early intervention, we work with young people to provide support at a crucial time in their lives – to help get them back on track and strengthen their ability to manage their mental health in the future.

Jacob's Well: National Vocations Awareness Week

August 2 to 9 marks National Vocations Awareness Week across Australia. It is an opportunity to engage with the vocational expressions within the Church in Australia. The Vocations Office of the Province of Australia has produced this attached resource for this week.

This resource offers some reflection materials on the life of the Marist Brother. In particular, it launches three videos on three aspects of our life: Mission, Community and Spirituality. These videos were visioned, created, actioned, and produced by Conor Ashleigh, a visual storyteller and communications consultant who has journeyed with numerous Marist communities around the world for many years. His passion and insight into the realities of our world have captured the modern context of the Marist Brother in Australia in a stunning and meaningful manner.

These media presentations will also feature in our social media platforms during this week. Please feel free to check out these platforms, browse our content, and witness the contemporary expressions of Marist Brothers life in Australia. Details of our platforms are listed on the last page of this resource, or search for “Marist Brothers Life” on Facebook and Instagram. Coupled with these videos are some written resources and imagery that offer complimentary perspectives on the life of the Religious Brother.

My invitation to each of you is to spend some time this week reflecting on the beautiful whispering of God in your heart and to God’s invitations in your life. Some questions may assist you:

What are I being called to do at this time?

What are I being called to be?

How do I want to live my discipleship of Jesus more fully?

What expressions of my discipleship am I being called to?

What expression of Christian, Marist and/or religious life am I being called to?

Jacob's Well: Marcellin and his maternal influence(r)s

In this age of social media, the role of an influencer is a source of income for some, and a source of inspiration or guidance for others, for better or worse. There might be people on your feeds that you specifically follow out of interest, or in search of deeper connection with them. Good for you! However, this form of profession has always been with us throughout history: people who, by their example, advice or behaviour, change the way others see or act. Their identification in our lives, and in the lives of other people, whether for good or bad, is important.

A return to Marcellin. A little history about Marcellin, and the women that influenced his life. It is not a coincidence that Marcellin had a strong devotion to Mary: his lived experience was one of being surrounded by courageous, intelligent, faithful and powerful women.

This week, I wanted to share some stories of these women in Marcellin’s life.

From Br Lluís Serra Llansana, (2001), “Founder of the Institute of the Marist Brothers”:

While political events unfold, Marcellin lives a close relationship with his mother. Mrs. Champagnat is involved with the silk and lace trades, and she expands the family income by farm work and milling. Marcellin's mother, Marie Therese, exercises a moderating and calming influence upon her husband activities. A few years older than her husband, her forceful character and her competence in managing home and children make it easier for her to fulfil her obligations. She raises her children carefully, putting the emphasis on piety, social relations and a spirit of thrift. Louise Champagnat, Marcellin's aunt, is a Sister of Saint Joseph. She was expelled from her convent in the Revolution. The influence she leaves upon Champagnat by her prayer, teaching and good example is so marked that he will frequently remember her with pleasure and gratitude. When he is seven years old, Marcellin asks, "Aunt Louise, what is the Revolution? Is it a person or some kind of wild animal?" In the environment of the time, one could not but feel the pulse of history. Marcellin's upbringing unfolds at the intersecting point where the new ideas introduced by his father meet the deep, traditional religiosity represented in his mother and aunt. At the heart of the family, problems are experienced in all their intensity, and find their resolution through a spirit of moderation, one that is more at the service of people than of ideology. There prevails a spirit of community, a closely-knit bond among the brothers and sisters.

Another story from Br Lluís Serra Llansana, “Marcellin's Pilgrimage to Lalouvesc”:

In the summer of 1803 two recruiters for the priesthood visited the Champagnat family to see if any of the boys in the family might consider the priesthood. When the proposal to train for the priesthood was presented to the three sons, it was only Marcellin who showed interest. The one great drawback was that Marcellin was almost illiterate. His father thought this to be too great an obstacle and repeatedly questioned the lad on his intentions but Marcellin's mind was made up: he thought only of becoming a priest.

Marcellin was 14 years old... his decision to enter the priesthood caused him to do some study under his brother-in-law Benoît Arnaud, married to Marcellin's sister, Marianne. Formerly, Arnaud had been a seminarian. Marcellin made little progress in his studies whilst staying with his brother-in-law over two years. Benoît decided to tell Marcellin to forget about studying and to do something else. However, this failed to shake Marcellin's determination. He prayed harder invoking the intercession of St John Francis Regis.

Finally, Benoît brought him back to his mother, declaring that he could not agree with Marcellin's going to the seminary. Yet the more the obstacles piled up in his path, the more determined Marcellin became in his vocation.

His mother, seeing her son's determination suggested a pilgrimage to Lalouvesc (or La Louvesc), in the conviction that they would find help at the shrine of St John Francis Regis. For this Pilgrimage they walked the 40km from Marlhes to Lalouvesc and back in three days. When they returned, Marcellin declared that he had made up his mind to go to the seminary. He was sure it was God's will for him to do so.

Br Seán D. Sammon, (1999), “A Heart That Knew No Bounds”: