Jacob's Well: Marian Resources

With the recent celebration of Mother’s Day, and the traditional honouring of Mary, the mother of Jesus during May, it is timely to offer some practical Marian resources. While Jesus remains the centre of our shared Marist spirituality, Mary's leadership, model, and humanity also form part of deepening our relationship with God. May these resources, with their utility spanning from primary-aged children to adults, aid your ministry.

May the Month of Mary Resources (Education Secretariat Archdiocese of Dublin, Ireland)

These resources, provided by the Catholic Archdiocese of Dublin, provide PowerPoints and simple written resources on Mary and the Rosary. The site also contains links to other useful sites on the Rosary and Our Lady of Lourdes. It is principally aimed at primary education.

http://education.dublindiocese.ie/may-the-month-of-mary-resources/

Marian Resources (Loyola Press, USA)

Loyola Press is a non-profit Catholic publishing ministry of the Society of Jesus (the Jesuits) in the USA. This site contains a wealth of free downloads and links on a variety of topics including; the story of Mary, intergenerational event about Mary, Marian activities, Marian celebrations and feast days, the Rosary, prayers and mysteries, Marian prayers, and other information about Mary.

Marian and Mission Resources (Mission Together, UK)

Mission Together is the children’s branch of Missio, the Catholic Church’s official children’s charity for overseas mission in England and Wales. These resources, aimed for primary-aged children, include prayers and practical activities for assemblies that connect to the Church's mission.

https://missiontogether.org.uk/calendar/marian-and-mission-rosary/

Hail Mary: Reflections on The Mysteries of the Rosary (Br Mark O’Connor and the Marist Association of St Marcellin Champagnat)

If you haven’t seen this already, these recently released resources provide substantial material for prayer and reflection during this time. Follow the link to subscribe, and check out more resources on the Association’s website.

Jacob's Well: Short Films for Ministry

In our ministry, and our Christian tradition, stories have the power to inspire, motivate, heal, and challenge us. The gift of telling our own story is precious and powerful. There are so many wonderful storytellers in our lives and our world, especially in a format uniquely its own: short films and stories.

These pieces of art capture some of life’s most important and poignant moments, communicating and resonating with our own lives. Inspired by the many cinematic stories that currently exist, as well as the ones that have touched our hearts, here are some resources for short films that might spark an idea or helpful in your ministry.

Float

Pixar is a giant of short animated filmmaking, with scores of short movies produced with stunning results. This is one of my favourites: a film about a father who was afraid to let his son be himself. Pixar Animation Studios and the SparkShorts filmmakers of FLOAT released this film in solidarity with the Asian and Asian American communities against Anti-Asian hate in all its forms in the USA. Its universal message of allowing others to be themselves and live their freedom is beautiful. Check out other more recent films like “Wind” and “Bao” as well!

Coin Operated

Looking for motivation? This movie is about a young boy who is obsessed with a spaceship and has always wanted to get to the moon. This short movie is a brilliant display of a child’s vivid imagination. It offers a lesson to not give up despite all the barricades you face in life. The young boy has an undying passion and determination to fulfill his ambition. He stays on his ground and devotes his entire lifetime in pursuing the dream.

Hair Love

Hair Love tells the story of an African-American father trying to help his daughter comb and styling her hair for the very first time. On the surface. This story is about family, overcoming struggles, and the gift of love.

Zero

This moving Australian film tells a complex, but all too familiar story of exclusion and intolerance. Using imagery of numbers and a world made for yarn, its messages of acceptance and that all of us have something unique to offer the world, regardless of our nationality, offers important points for reflections.

Stone Soup

Based on Marcia Brown’s famous story, animated versions of ‘Stone Soup’ bring to life this timeless story of selfishness, generosity, and the power of community. The version produced by SBS is one of my favourite tellings.

https://www.sbs.com.au/ondemand/watch/11719747826

Happy viewing!

Jacob's Well: Marist Patrimony

The Marist family is blessed with a rich history. For over two hundred years of the Marist Institute, the stories, documents, reflections, and people that have followed in the footsteps of Marcellin Champagnat have been preserved, interpreted and shared. While the conservation of history, in itself, is an important pursuit, recognising that our contemporary expressions of Marist life are in conversation with our past, both consciously and unconsciously, is also vital to acknowledge.

As part of a request by a team member, here are two interesting and well-researched articles into significant aspects of Marist history: historical sources of Marist spirituality and a history of l’Hermitage in France.

Historical sources of Marist spirituality by Br Michael Green

This extensive article is the culmination of a series of reflections written by Australian Marist Brother, Br Michael Green, in 2020. For many of us, the five characteristics of Marist education have become the standard banner for all things Marist in Australia. For Champagnat, these specifics depictions of Marist spirituality would be unrecognisable to him, even though the spirit and sense of the characteristics were part of the initial expression of Marist life during Marcellin’s lifetime. Br Michael explains the context of the modern expressions of Marist spirituality and their origins within the background of our history.

Illustrated History of Notre Dame de l’Hermitage, St. Chamond, Loire, France by Br Barry Lamb

Notre Dame de l’Hermitage, an extensive property located in the Gier valley between the Monts du Lyonnais to the north and Mont Pilat to the south, remains a central location for many Marists across the world. Considered as one of the spiritual homes of the Marist Brothers, its history is intimately connected to the lives of people who have animated the Marist story in communities and ministries throughout our history. Br Barry’s book offers another perspective on this unique and beautiful place of renewal and inspiration.

Jacob's Well: Resources for Daily Prayer

It has been just over a year since communities and countries across the world entered their first lockdowns of the COVID-19 era. How different does the world look one year on! Instead of house churches and televised masses, Holy Week for 2021 is already looking considerably dissimilar. However, the invitation for prayer and reflection remains the same: to enter deeply into the life of Jesus Christ, continuing the ongoing work of God within us and around us, in profound transformation, deep conversion, and unconditional love.

The Christian life isn’t a process of overnight revolution, but rather a choice made every day to walk through life in relationship with God, others, and creation, centred in the person of Jesus Christ. Some days, this feels easier and more natural than others. On these other days, it can be a real and heart-wrenching struggle. The encouragement of prayer, that daily practice of authentic conversation with God, is a key part of that journey. Praying with scriptures, or the reflective musings of other people, can be significant aids to one’s own personal prayer practices. Here are some meaningful resources that might help you with your daily prayer.

Abide: Keeping Vigil with the Word of God (Macrina Wiederkehr OSB)

This beautiful book contains reflections of specific scripture passages that are gentle, profound and substantial. Here is an excerpt from the publisher’s description:

In the Gospel of John Jesus directs us, Abide in me, as I abide in you. This book is an invitation to make the Word of God your home through the practice of lectio divina. Macrina Wiederkehr, OSB, encourages you to turn the words of Scripture over in your heart as a plough turns over the soil to welcome the seed.

In these scriptural meditations, the piercing reflective questions and personal prayers lead the reader into a deeper relationship with the Divine. Aware that drawing near the Word of God requires a special kind of presence, the author invites you to breathe in the Word, wait before the Word, walk through the pages of Scripture as a pilgrim, and, finally, abide in an intimate and transforming communion with God.

The format of the book lends itself not only to daily personal prayer and reflection, but to group faith sharing as well.

Prayer for Each Day (Taizé Community)

The Taizé community, an ecumenical religious order, engages with prayer through the use of repetitive chants and scriptural passages. This book provides a series of different prayer services for use throughout the year for personal and communal prayer. These prayers are also available on its website: Prayer for Each Day.

An excerpt from the publisher’s description: Each of these prayer services for the different times of the year contains a psalm, a choice of Bible readings, intercessions and a choice of closing prayers. A detailed introduction gives practical suggestions for preparing a time of prayer in the style of Taizé.

You Are the Beloved: Daily Meditations for Spiritual Living (Henri J. M. Nouwen)

The writings of Henri Nouwen are often used as a significant example of twentieth-century Christian mysticism within a Western context. This compilation of some of his writings provides daily reflections that reflect a deep personal relationship with God and an invitation to be immersed in the same world.

An excerpt from the publisher’s description: This daily devotional from the bestselling author of such spiritual classics as The Return of the Prodigal Son and The Wounded Healer offers deep spiritual insight into human experience, intimacy, brokeness, and mercy.

Nouwen devoted much of his later ministry to emphasizing the singular concept of our identity as the Beloved of God. In an interview, he said that he believed the central moment in Jesus's public ministry to be his baptism in the Jordan, when Jesus heard the affirmation, "You are my beloved son on whom my favor rests." "That is the core experience of Jesus," Nouwen writes. "He is reminded in a deep, deep way of who he is. . . . I think his whole life is continually claiming that identity in the midst of everything."

You Are Beloved is a daily devotional intended to empower readers to claim this truth in their own lives. Featuring the best of Nouwen's writing from previously published works, this devotional will propel the canon forward as it draws on this rich literature in new and compelling ways. It will appeal to readers already familiar with Nouwen's work as well as new readers looking for a devotional to guide them into a deeper awareness of their identity in Jesus.

An Ignatian Book of Days (Jim Manney)

An excerpt from the publisher’s description: Jim Manney’s latest book is an invitation to clearly see, feel, and experience God’s presence through an Ignatian lens in our daily lives. The only 365-daily reading book written explicitly from the point of view of Ignatian spirituality, An Ignatian Book of Days guides us to find God in all things, every day.

Manney writes in the preface: “I don’t try to define the Ignatian point of view. Rather, I try to share it. I wanted to find the most compelling Ignatian voices and let them speak for themselves. I’ll let Ignatius Loyola and the many great thinkers, writers, and saints who followed in his footsteps show you what Ignatian spirituality is.”

Jacob's Well: Literature for Crafting Ministry Skills

I love the image of God as a Potter. It is an ancient biblical image, one that highlights God’s care, passion, individuality, and artistry in our loving creation. We are beautifully and wonderfully made, as Scripture tells us, through this process of crafting. In the same way, we are invited to be part of our ongoing and dynamic growing, in the actions we take and the choices we make. In our ministry, it is reflected in the deliberate ways that we craft our skills, perspectives and ideas with intention and love. How are you choosing to mould yourself? As a launchpad from this, here are some resources that span perspectives and wisdom that may aid you as you craft, more deeply, your ministry skills.

Back-Pocket God: Religion and Spirituality in the Lives of Emerging Adults by Melinda Lundquist Denton, Richard Flory, and Foreword by Christian Smith

One of the most fundamental lessons in engagement in any field is knowing your audience. In youth ministry, there are a number of insightful and detailed collections of data that can positively contribute to deeply understanding the faith perspectives of young adults. This book, Back-Pocket God builds on previous volumes grounded in the National Study of Youth and Religion from the United States of America. This study has followed the same group of young people over the course of a decade and provides a more nuanced story of emerging adults and their relationship with religion and spirituality than is available from recent books and other reports.

The Communication Book: 44 Ideas for Better Conversations Every Day by Mikael Krogerus and Roman Tschäppeler

Communication is a key skill across every profession. In youth ministry, the relationships that are formed and the dialogues in those relationships are central. Here is one resource that offers interesting and broad perspectives for working smarter in your professional environments. The authors have suggested 44 important communication theories ranging from Aristotle's thoughts on presenting, through Proust on asking questions, to the Harvard Negotiation Project. A fascinating read!

100 Ideas for Teaching Religious Education by Cavan Wood

Looking for something for application in designing and implementing workshops and educational opportunities? While the book is targeted to new and experienced teachers alike, it contains 100 inspirational ideas on teaching and engaging with religious education for a number of contexts. Its practical focus can serve as an important stimulus for a range of activities and sessions across ministerial settings.

Sacred Stories, Spiritual Tribes: Finding Religion in Everyday Life by Nancy Tatom Ammerman

We know the power of people’s story. Deep listening to a person’s truth is one of the most important gifts we can offer one another. This book offers this opportunity in a beautiful and gentle manner. Here is some information about this engaging book:

Nancy Tatom Ammerman examines the stories Americans tell of their everyday lives, from dinner table to office and shopping mall to doctor's office, about the things that matter most to them and the routines they take for granted, and the times and places where the everyday and ordinary meet the spiritual. In addition to interviews and observation, Ammerman bases her findings on a photo elicitation exercise and oral diaries, offering a window into the presence and absence of religion and spirituality in ordinary lives and in ordinary physical and social spaces. The stories come from a diverse array of ninety-five Americans across a range that stretches from committed religious believers to the spiritually neutral. Ammerman surveys how these people talk about what spirituality is, how they seek and find experiences they deem spiritual, and whether and how religious traditions and institutions are part of their spiritual lives.

Jacob's Well: Marcellin's Miracles

As many of you know, becoming a saint is not easy! While sainthood often appears to be out of our reach, the original meaning of saint was much more accessible and attainable. In the first few centuries of Christianity, the term saint was used to refer to all followers of Christ or the people of God. Scripturally, in the New Testament, the writing of Peter, Luke, and Paul all reflected a broader use of the understanding of saint, albeit with slight differences in connotation. As time passes, the term became more exclusive in its use, singling out individuals who exhibited qualities of discipleship that were noteworthy or inspirational, whether in their life or in their witness as martyrs.

Prior to the year 1234, the Church did not have a formal process to recognise a saint, now called the process of canonization. During this time, a local bishop or church could designate someone a saint, and often their veneration would seep into the official records of saints decades or centuries later. Often, people of legends, or some very dubious people, were designated as saints. In 1234, Pope Gregory IX established procedures to investigate the life of a candidate saint and any attributed miracles. In 1588, Pope Sixtus V entrusted the Congregation of Rites (later named the Congregation for the Causes of the Saints) to oversee the entire process. Beginning with Pope Urban VIII in 1634, various Popes have revised and improved the norms and procedures for canonization.

In brief, the current process of canonisation goes a little like this:

One of the more interesting parts of the process in the recognition of the miracles needed, after their death, during the beautification and canonisation stages. Only one miracle is needed for each of these stages and the process of confirming these miracles is long, thorough, and complex. Maybe I can cover that one in a future edition! For Marcellin Champagnat, he has the honour of THREE recognised miracles. The first two came during his process of beautification. These were the October 1939 cure of Mrs Georgina Grondin from a malignant tumour in Waterville, Maine, USA, and the 12 November 1941 cure of John Ranaivo from cerebrospinal meningitis, in Antsirabe, Madagascar. Details of these miracles are difficult to find, but a Papal Decree recognizing these two cures as miraculous was issued on the 3rd May 1955. Pope Pius XII proclaims Marcellin Champagnat Blessed, in St Peter’s Basilica, Rome just under one month later, on 29th May 1955.

Marcellin’s third miracle, the one that elevated his recognition to sainthood, took place in July 1976, with the cure of Br Heriberto Weber Nellessen, in Montevideo, Uruguay. However, it would take another 25 years for the investigation and confirmation to take place. Here are some details about Br Heriberto and his cure:

Br Heriberto (Heinrich Gerhard Webber) was born at Essen (Germany) on 19 March 1908. After his novitiate and first profession in Furth (21 November 1926) and a period of teacher training he taught for a few years in Germany. On 30 April 1937, owing to difficulties arising in his country, he had to go into exile in Uruguay, along with a large group of German Brothers. He was to develop his apostolic activity for many years in Uruguay, first in Primary teaching and then in Secondary. On several occasions he discharged the duties of College Headmaster and Superior of Community.

In May 1976, in the midst of his normal activities, he was afflicted by fevers reaching high temperatures and experienced severe spinal pains which forced him to stay in bed. The doctors diagnosed “an early, unknown growth which was transferring to the lungs”. The doctors who were attending to him pronounced him incurable and as such he was treated in the sanatorium where he remained as a patient.

On 13 June, at the request of the Brother Provincial of Uruguay, the Brothers of the Province, together with their pupils, started a novena of prayers to ask for the cure of Br Heriberto through the intercession of Blessed Marcellin Champagnat. At the end of the novena, on 26 July 1976, the patient felt a sudden and unforeseen improvement. The X-ray plates taken on that date showed that the signs of the illness had disappeared. Br Heriberto, the Brothers of the communities in Uruguay and the pupils who knew him, from the very beginning considered this cure to be miraculous.

Find out more here at the source: https://champagnat.org/en/marist-institute/founding/the-miracle-for-the-canonization/

This final miracle was recognised by the Pope in January 1999, and Marcellin was officially declared a saint in April 1999.

A little prayer can go a long way!

Jacob's Well: Lenten Resources

Online Lenten Resources

As we enter the first week of Lent, you may have been caught off-guard by the sudden arrival of the season! If it has, like it has for me, then maybe a collection of Lenten resources could help you enter more deeply into the season. Here are some contemporary resources from several diverse sources. I hope they are helpful!

As always, the beautiful words of Pope Francis, from this Lenten message for 2021, captures the heart and spirit of the Lenten seasonal invitations:

Dear brothers and sisters, every moment of our lives is a time for believing, hoping and loving. The call to experience Lent as a journey of conversion, prayer and sharing of our goods, helps us – as communities and as individuals – to revive the faith that comes from the living Christ, the hope inspired by the breath of the Holy Spirit and the love flowing from the merciful heart of the Father.

May Mary, Mother of the Saviour, ever faithful at the foot of the cross and in the heart of the Church, sustain us with her loving presence. May the blessing of the risen Lord accompany all of us on our journey towards the light of Easter.

The National Council of Churches in Australia is a national organisation that works in partnership with state Christian ecumenical councils around Australia. They are an ecumenical body, working to provide spaces of dialogue for Christian denominations to find common ground in faith and to pray together in a spirit of fraternity. They offer many links to free online Lenten resources, including Lenten reflections for 2021. The library can be found here:

https://www.ncca.org.au/ncca-newsletter/february-2021-1/item/2360-lenten-resources-2021021

Godspace, an online space for Christian spirituality, is organised by a husband-and-wife team of Christine and Tom Sine. They have collected an eclectic and considerable amount of Lenten resources across a number of Christian perspectives. Although dated 2019, the site was recently updated to include videos, reflections, and links to numerous current resources. Have a gander here:

https://godspacelight.com/2019/02/12/resources-for-lent-the-latest-for-2019/

From the USA, the Marist Fathers have produced a calendar of daily reflections for Lent, drawing on elements of our shared Marist spirituality for the season. The link to the calendar is here: https://www.societyofmaryusa.org/content/uploads/2021/02/Lenten-Calendar_2021_F.pdf

America Magazine, one of the world’s leading English-language Catholic publications, is providing substantive reflections on Lent for 2021. Check out the current resources, and regular updates, here: https://www.americamagazine.org/lent2021

On the international website for the Marist Brothers, there are collections of prayers and resources offered across our Marist spirituality and for the liturgical seasons. By far the largest collection of resources are provided for Lent, so check them out here: https://champagnat.org/en/library/prayers/

Jacob's Well: Marcellin and the Hermitage

A new year and a new Jacob’s Well! Well, February still feels like the year is getting into gear, so it seems like a fitting time to begin our resource sharing again on this platform.

As 2021 currently unfolding on its own terms, whilst still amid this particular pandemic environment, I thought it could be helpful to draw inspiration from St Marcellin during a significant time in his life. There have been a few occasions where Marcellin, faced with extreme adversity, surrounded by events outside of his control and seeking to put his wild dreams into action, took bold and unexpected undertakings. Drawing on his deep well of faith in God, heartened by a community that trusted him and navigating a myriad of perspectives that sought to temper, change or disapprove of his ambitions, Marcellin Champagnat chose to forge a legacy that continues to inspire, shelter, and care for Marists today. This is the story of the building of the Hermitage, France.

Once again, we seek the perspective of Br Jean-Baptiste Furet, from his biography of Champagnat, to tell the story of the construction of his wild and precious project. It is a story of ambition and folly, discouragement and affirmation, doubt and faith, hope and triumph. The building of the Hermitage was not a simple, inevitable, or romantic task. It required hard work, persistence, community, prayer, and determination. Many people thought it was the wrong type of project, in the wrong place, at the wrong time, with the wrong people. They may have been right, partially. However, the Hermitage has become more than a building: it is a home, a place of faith, a meeting space for family, and a place of beauty, tranquillity, and peace. This is the chronicle of its origins.

On his journeys to Saint-Chamond, Father Champagnat had often let his eyes rest on the valley where the Hermitage now stands. More than once, he had thought of it as a novitiate site, with its deep solitude, its perfect tranquillity and its great suitability for studies. "If God blesses us", he reflected, "We could very well set up house there." Yet, before finally opting for that position, he combed the surrounding district with two of the principal Brothers, to make sure that it was the best available. When he had had a good look at it all, it seemed the most suitable location offering for a religious house.

The valley of the Hermitage, divided and watered by the clear waters of the Gier, bounded on the east and west by an amphitheatre of mountains, covered almost to their peaks with verdure or with oak and fruit trees, is certainly a charming spot, especially in summer. But its restricted area, making it difficult to cater for a large Community there; the breezes and mists associated with the waters and decidedly uncongenial to weak constitutions or to health enfeebled by the exertions of teaching; these would be factors that would later force the chief House of the Institute to be moved elsewhere.

Human wisdom would see a strange imprudence in Marcellin's undertaking to construct such a costly building, while he was entirely without funds. The land alone cost him more than twelve thousand francs. Naturally, then, when it became public knowledge that the community was moving and that a vast building was to be put up, there was a new storm of reproach, criticism, insult and abuse. This one perhaps surpassed even the outburst at the most turbulent time of the Institute. It was in no way abated by the Archbishop's approval of the work, or by his high opinion of the Founder and good-will towards him. Nothing, in fact, could calm the agitated minds or silence the malicious tongues. His plan was regarded as sheer madness, and even his friends heaped blame on him and left no stone unturned to try to dissuade him. Alas! the world has no insight into the works of God, because they transcend its intelligence, clouded as it is by passion. The world treats these works as folly and their promoters, as madmen. "The world", says St. Paul, "treats us as fools." Such was the treatment meted out to Christ in the court of Herod; his servants should expect no better.

"That mad Champagnat", alleged several of his fellow-priests and many other people, "must have gone off his head. What does he think he's doing? How is he going to pay for that house? He must be extremely rash and have lost all judgment to be blind enough to conceive such plans." A Lyon bookseller had secured a loan of twelve thousand francs for Father Champagnat so that he could start the construction. This man called, on business, at a presbytery near Saint-Chamond and was invited to dinner by the parish priest.

On that day, there was a sizable gathering of priests, one of whom bantered on seeing him: "Well, sir, you seem to have got rid of your money?" "What do you mean, exactly?" was the reply. "The news is", continued the other, "that you have just lent twelve thousand francs to that fool of a Champagnat." "I haven't really lent it", corrected the book-seller, but I procured it and went surety for him." On saying this, he was reproached with having made a big mistake. When he asked why, he was told: "Because that man is reckless and stubborn; pride alone drives him, precipitating him into an undertaking which is doomed." Having protested that he had a higher opinion of Father Champagnat than the one expressed, that he believed he was a good man and that God would bless him, the book-seller was assured: "No, no; that's impossible; he is a hopeless man: no knowledge, no money, no ability. How could he possibly succeed? Hounded by his creditors, one day he will have to abandon ship and make off. It was unwise of you to stand surety for him; you only encourage his foolhardiness and put your money in jeopardy." "I hold Father Champagnat in high esteem", was the persistent response. "I have the utmost confidence in him and am convinced that this work will succeed. If I'm wrong, too bad! So far I have not regretted having helped him and I still believe that I shall never have to do so."

Father Champagnat was well aware of what people were thinking, and saying about him in public; but the talk of men had little influence on him, and he did not invoke the principles of hum on prudence to guide his life. So it was, that despite the large Community on his hands, despite a debt of four thousand francs, despite a lack of money, and with his confidence, (an unbounded one), in God alone, he fearlessly took on the construction of a house and chapel to accommodate one hundred and fifty people. The construction and the land purchase cost him more than sixty thousand francs.

This action certainly flew in the face of human prudence. No wonder that the carrying out of his plans drew so much fire on their author! However, to cut costs, the whole Community worked at the construction; even the Brothers engaged in the schools were summoned to the task. It was a competition in zeal and devotedness with neither the weak nor the sick willing to refrain. One and all wanted the satisfaction of having a share in constructing a building which was so dear to them. There was one difference from the La Valla construction, in which the Brothers had done even the masonry. Masons alone now did this work, while the Brothers quarried and carried the stones, dug sand, mixed mortar and laboured for the stone-layers.

Towards the beginning of May, 1824, Father Cholleton, Vicar General, came to bless the foundation stone of the new building; and such were the bareness and poverty of the House, that nothing could be found to give him for dinner. The Brother cook went up to Father Champagnat and asked: "What am I to do, Father, for I have absolutely nothing to give Father Cholleton." Reflecting for a moment, he replied: "Go and tell Mr Basson, that the Vicar General and I are going to dine with him." That Mr Basson, who was rich and a great friend of the Brothers, welcomed them with pleasure. Moreover, this was not the only time that Father Champagnat called on him for such a service. He did so each time he found himself in a similar quandary.

To house the Brothers, Marcellin rented an old house on the left bank of the Gier, facing the one under construction. The Brothers slept in an old garret so narrow that they were crowded on top of one another. Their food was of the simplest and most frugal variety. Bread, cheese, a few vegetables sent along occasionally by generous people from Saint-Chamond, very exceptionally a piece of pork, and invariably plain water for drink: that was their style of life. 'Father Champagnat shared the conditions of food and housing, often accepting even the worst, for himself. For example, as no space could be found in the house for his bed, he was forced to put it on a kind of balcony, exposed to the onslaught of the wind and sheltered from rain only by the eaves. That's where he slept throughout the summer, and in winter he retired to the stable. The Brothers and their Founder underwent great hardship for almost a year, while they lived in that house, which was in a sad state of repair.

Right through the time of construction, the Brothers rose at four o'clock in the morning. Father Champagnat himself gave the rising signal and, when necessary, lit the lamps in the garret. Having risen, the Community gathered amongst the trees, where Marcellin had constructed a small chapel in honour of the Blessed Virgin. A chest of drawers served as both vestment press and altar; for bell-tower, there was an oak-tree on whose branches the bell was hung. Only the celebrant, the servers and the principal Brothers could fit in; the others remained outside. All prayed there, before an image of the Mother of God. Such was their fervour that they seemed oblivious of all else, and the only noise was from the rustling leaves, the murmuring of the waters a little way off and the song of the birds.

Each morning, the Community went to the chapel, said morning prayers, made a half-hour's meditation and assisted at Holy Mass. -After lunch, they went there again to make a visit to the Blessed Virgin and in the evening, they closed the day by a recitation of the rosary. Many a time, travellers along the road which skirted the mountain opposite, came to a stop, looked this way and that, wondering where those voices were coming from, singing as one and with such vigour. It was the Brothers, hidden amongst the trees and kneeling before the little altar on which the spotless Lamb was sacrificed, to the accompaniment of hymns of praise to Jesus and Mary.

Mass over, each went off to his work, giving it all his energies, in silence. On the hour, a Brother appointed to do so, rang a little bell. Then work was interrupted, each recollected himself, and together they recited the Gloria Patri, the Ave Maria and the invocation to Jesus, Mary and Joseph. No need to say that Father Champagnat was always first to work; he arranged everything, assigned the tasks, and maintained a general supervision. None of this prevented him, according to the opinion of the workers themselves, from accomplishing more stonework than the most skilled of them. As we have already indicated, the Brothers were excluded from that work, but the masons did allow Marcellin to do it, because he was a master of the trade. Often, he could be seen still building and working alone during the short siesta taken by workers, and again in the evening when the others were gone. At night, he said his Office, made out his accounts, marked the workmen's time sheets, listed the materials supplied that day, and planned the next day's work. It is clear, then, that he had very little time for rest.

It is worth pointing out that no Brother or other workman employed by Marcellin, was ever in an accident. This should be seen as a particular protection of God for the Community, especially as Father Champagnat spent his whole life building and always involved the Brothers in this kind of work. Quite often, serious accidents threatened the Community, but divine Providence, through Mary's intercession, always halted or averted the harmful effects. Let us take a few examples.

A workman, building at a great height on the side of the house next to the river, fell, and was headed for giant stones below, where he would have been dashed to pieces. On his way down, with the scaffolding materials, he was lucky enough to brush against a big tree and seize one of its branches, on which he hung till help came. Re wasn't harmed, not even scratched. The protection of God is even more evident from the fact that the wood of the tree was brittle and the branch so weak that it couldn't normally support such a weight.

A young Brother, attending the masons on the third storey of the building, was walking on a rotten plank which gave way under him, causing him to fall. As he dropped, he called on Our Lady's help and remained hanging by one hand, his entire body below the scaffolding. His situation was so dangerous, that the first workman to come to his rescue didn't dare approach him or touch him. A second, more fearless and generous, rushed forward, grasped the Brother's hand and pulled him back. The only harm he suffered was an extreme fright.

Ten or so of the strongest Brothers were carrying up stones to the second storey. One of them, having reached the top of the ladder with an enormous chunk on his shoulders began to feel faint under the weight of the heavy burden. His strength failed and the stone fell capsizing the Brother following, who was knocked to the bottom of the ladder. A slight movement of the head on his part, even though he was unaware of any problem, meant that he was simply grazed instead of having his head shattered. Father Champagnat, a witness of the incident from up above the ladder, considered his death as a foregone conclusion and gave him absolution. Yet he was not harmed, only so frightened that he ran around in the field as though out of his mind. All the Brothers present shared his fright, as did Father Champagnat, who immediately had prayers of thanks said for the protection God had just shown the Brother. Next day, he again offered Mass for the same intention.

Although overburdened with work, Father Champagnat always found time, bath at night and on Sundays, to give the Brothers instruction and spiritual formation. During that summer, he thoroughly instructed them on the religious vocation, on the end of the Institute and on zeal for the Christian education of children. Sustained and invigorated by these instructions, the Brothers displayed admirable piety, modesty, devotedness and energetic effort during the entire time of the construction. The workmen were unstilted in their admiration for the spirit of sacrifice, of humility and of charity that prevailed amongst the Brothers; so much so, that their admiration was given clear public expression. The good example of the Brothers was not lost on the workmen themselves who, having admired them, did their best to imitate them. Hence, they, too, soon became silent, modest, reserved in their speech and full of consideration and kindness towards one another.

However, with the approach of All Saints, thought had to be given to sending the Brothers back to the schools. Father Champagnat preached them an eight-day Retreat, suggesting to each the resolutions befitting his needs, his defects, his character and his responsibilities; each one was to head his list of resolutions with the constant recall of the presence of God.

Two new schools were opened during that year. The one at Charlieu was requested by the Archbishop. The parish priest, Father Térel and Mr Guinot, the mayor, paid the initial expenses and proved to be lasting protectors and benefactors of the Brothers. The children were found to be in great ignorance and a prey to all vices that normally accompany it. For some time, their task was a difficult and thankless one, but their zeal, devotedness and patience triumphed completely in the end and that school became one of the most flourishing in the Society.

The second school founded at this time, was that of Chavanay. The parish priest, Father Gaucher, presented himself in person to request Brothers, and accepted responsibility for some of the initial expenses of the foundation. The people of Chavanay were most enthusiastic about having the Brothers. A delegation of leading men was sent to the Hermitage to accompany them to their residence, and the school, with the total backing of the people, was attended from the start by all the children of the parish.

About the feast of All Saints in 1824, Father Champagnat was released from his duties of curate at La Valla. Up till then, on Saturday evenings during the construction, he went up to La Valla to hear confessions and to say Mass on Sunday. Now that he was free from all commitment outside his project, he gave himself exclusively to the service and welfare of the Community.

Winter was passed on work inside the house. As he usually did, Father Champagnat led the workers, the carpenters, the plasterers, etc; The work went ahead at such a pace, that in the summer of 1825, the community was able to take up residence in the new house. The chapel , too, was completed and readied for divine service. Father Dervieux, parish priest of Saint-Chamond was delegated by the Archbishop to bless it, which he did on the Feast of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin. That holy priest, whose feelings towards Father Champagnat and his Congregation had changed, presented a set of candlesticks for the chapel and they were used at the blessing.

Jacob's Well: Marcellin and Advent

The season of Advent offers substantial amounts of reflective materials, both on the readings of the significant Sundays of these times and the images and stories that prepare us for Christmas and the birth of Jesus. For Marists, looking at the way that St Marcellin reflected on Advent can give us keen insights in his complex character, as well offer some personally reflective resources.

Marcellin was known to draw upon the common Christian spirituality of the era, that drew on the three images of the Crib, the Cross and the Altar as the three most important aspects of the life, message and person of Jesus Christ. His devotion to Jesus is well documented, including in this passage from the Br Jean-Baptiste Furet biography:

“To know, love and imitate Jesus Christ: that is the sum of virtue and of holiness. Father Champagnat knew this truth well and constantly resorted to the life of our divine Saviour for the subject of his meditations. He had a particular devotion to the Child Jesus and each year prepared carefully for the feast of his birth, celebrating it with all possible solemnity. On Christmas eve, he would have a crib made, to represent that divine birth with its accompanying circumstances; he joined with the community in adoring the divine Child lying in the crib on a little straw and addressed to him the most fervent prayers.

"Oh, Brothers", he exclaimed when talking about this feast, "look at the divine Child, lying in a crib and completely helpless; his tiny outstretched hands invite us to approach him, not so that we can share his poverty, but so that he can enrich us with his favours and graces.

He became a child and reduced himself to this state of abjection so that we might love him and be free from all fear. There is nothing so lovable as a child; his innocence, his simplicity, his gentleness, his caresses and even his weakness are capable of touching and winning the hardest and cruellest of hearts.

How, then, can we not help loving Jesus, who became a child to stimulate our confidence, to demonstrate the excess of his love and to let us see that he can refuse us nothing? No-one is easier to get on with and more pliant than a child; he gives all, he pardons all, he forgets all; the merest trifle delights him, calms him and fills him with happiness; in his heart is neither guile nor rancour, for he is all tenderness, all sweetness. Let us go, then, to the divine Child, who has every perfection, human and divine, but let us do so by the path he took in coming to us, that is, the path of humility and mortification; we should ask him for those virtues, for his love and all that we need: he can refuse us nothing.".”

The only other substantive information that Br Jean-Baptiste Furet offers in his book about Champagnat during the Advent season is a reflection credited to Marcellin, reflecting on the Gospel from the second Sunday of Advent of that time, Luke 7:18-35. It provides a particular snapshot of Marcellin’s spirituality, which can be described, at times, as austere, context-specific and individually theological. It also provided an interesting insight into Marcellin’s personal faith and mindset:

We shall conclude the life of our venerated Father by summarizing an impressive instruction which he gave to the Brothers on the subject of constancy, while explaining the gospel for the second Sunday of Advent. "Constancy", he reminded them, “is a virtue that is absolutely necessary to a Christian to save his soul, and even more to a Religious to persevere in his vocation and acquire the perfection of his state. Our Lord's conduct in today's gospel is a convincing proof of this truth. The divine Master pronounces a magnificent eulogy of St John Baptist and before the assembled crowd, declares him to be the greatest of the children of men.

Now, what is it that he particularly praises in the holy Precursor? Is it his innocence, which was such that he probably never in his life committed even a single, fully deliberate venial sin? No. Is it his humility, which was so profound that he considered himself unworthy to untie the straps of Christ's shoes? No. The divine Saviour does not mention humility in his praise of St John. Is it his love of chastity, which led him to reprimand Herod fearlessly for his criminal behaviour? No. In this case; Jesus does not extol the virtue of chastity, however grand and sublime this virtue may be; all his praise is for the constancy of the holy Precursor.

To draw attention to the invincible firmness of St John, Our Lord questions those who surround him, and asks: 'What did you go out into the desert to see? A reed shaken by the wind? No; such a fickle and frivolous character, would not have been so great a spur to your curiosity and admiration. But, what did you go out to see? You went to see a man who is constant in the practice of the rarest and most heroic virtues; a man who never wavers in fulfilling the mission entrusted to him by God; who perseveres in the vocation and austere mode of life that he has embraced; who is steadfast in serving God, in edifying his neighbour, in reproving and correcting sinners and in supporting with unalterable patience and perfect resignation, the persecutions of the wicked: such is the man you went to see.

But why is Our Lord so lavish in his praise of constancy? Because, in some way, this virtue includes all the others and because the others are worthless without it. The important thing, according to St Augustine, is not to begin well but to finish well, for we have Christ's assurance that only the one who perseveres to the end will be saved. Besides, this virtue has to be practised every day and at every instant. In fact, the life of a Christian and still more that of a Religious, is a continual combat. To correct our defects, to practise virtue and to save our souls, we must do ourselves constant violence and struggle against all that surrounds us. We must struggle, for example:

1. Against ourselves, against our passions and our evil tendencies and against all our senses in order to maintain them in restraint and subjection.

2. Against the devil, that roaring lion who never sleeps, who is ceaselessly on the prowl to devour us; against that seducer of the children of God, that angel of darkness who transforms himself into an angel of light so as to hi de his snares 'and catch us more easily in his toils.

3. Against the world and its vanities, its maxims and its scandals; against the bad example of those of our confreres who neglect their duty and the prescriptions of the Rule; against relatives and friends so that we may not be motivated by considerations of flesh and blood, and may love them only in and for God; against those who make themselves our enemies, rendering them good in exchange for evil and, in this way, as the Apostle says, heaping coals of fire upon their heads.

4. Against all the creatures and objects around us, so that our hearts may not be attached to them and that, instead, we may use them simply as means to go to God and to work out our salvation.

5. Finally, we should struggle, with a holy violence, against God himself; we do this by our fervent prayers, by supporting with patience and resignation, the worries, dislikes, aridity, temptations and all the trials to which Providence may choose to subject us.

Now, only unshakable firmness and unflagging constancy can sustain us in such a violent and enduring struggle. It is too much for the inconstant, the faint-hearted and the cowardly; that is why the y are in great danger of being lost, and it is to them that Our Lord is speaking in these frightening words: 'Those who put their hands to the plough and look back, that is, those who are inconstant, are not fit for the kingdom of Heaven.

May your Advent continue to be a time of joy, peace, hope and love.

Jacob's Well: Movies for Ministry 2: The Sequel

Our professional year is drawing to its natural conclusion in the coming weeks. Advent is upon us, and it is one of my favourite times of the year. So, to mark this happy meeting of vocation and vacation, I thought we could return to some movies that serve both purposes. These films are perfect summer fare, as well as great preparations for ministries in the new year. Enjoy the continuation of movies…for ministry!

Clouds

The first recommendation is an emotional rollercoaster, but worth the ride. Based on a true story (for the book, Fly a Little Higher: How God Answered a Mom's Small Prayer in a Big Way by Laura Sobiech), young musician Zach Sobiech discovers his cancer has spread, leaving him just a few months to live. With limited time, he follows his dreams and makes an album, unaware that it will soon be a viral music phenomenon. The music is definitely retreat-able material, and there are many significant scenes that move and inspire. Clouds is available to watch on Disney+

Wit

This movie was highly recommended to me, and while I am yet to watch it, I trust its recommendation. The synopsis of the movie follows: Professor Vivian Bearing, an expert on the work of 17th-century British poet John Donne, has spent her adult life contemplating religion and death as literary motifs. Diagnosed with advanced ovarian cancer, she consents to an aggressive and experimental form of chemotherapy. Facing death on a personal level, she reflects on her life and work. Starring Emma Thompson, and released in 2001, its deep and confronting themes of life and death provide rich material for personal and communal reflection.

Wonder

Wonder (also known as Wonder: Auggie) is a 2017 American drama film directed by Stephen Chbosky and written by Jack Thorne, Steven Conrad, and Chbosky. It is based on the 2012 novel of the same name by R. J. Palacio. The film, which follows a boy with Treacher Collins syndrome trying to fit in, was released in the United States on November 17, 2017, by Lionsgate. A deeply moving movie, its themes of kindness, perspective, prejudice, joy and authenticity makes it a special movie to watch.

Little Boy

Little Boy is a 2015 World War II war-drama film directed by Alejandro Gómez Monteverde. The title is a reference to Little Boy, the code name for the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima, as well as a reference to the main character Pepper's height. I love this movie. The lead character is authentic and wins you over very quickly. With themes of hope, relationships, facing adversity, family and love, it has multiple applications in working with young people.

The Nativity Story

Finally, being the season of Advent, and loving Christmas almost as much as I love chocolate, I have to share one of my favourite movies for the season. The Nativity Story is a 2006 American biblical drama film based on the nativity of Jesus, directed by Catherine Hardwicke and starring Keisha Castle-Hughes and Oscar Isaac. We know the story: An adaptation of the Gospel accounts focused on the period in Mary and Joseph's life where they journeyed to Bethlehem for the birth of Jesus. It is beautiful. It is gentle, substantial, poignant and rousing all at the same time. Do yourself a favour and watch this film.

Happy Adventing!

Jacob's Well: Marist Leadership

With Student Leaders’ Gatherings buzzing around the country today, I thought I would offer a short reflection on some additional resources in the sphere of leadership. Our ‘Leading in the Marist Way’ program for young adults is filled with excellent resources, ideas, and inspirations for leadership, so while I am unable to match the brilliance and heights of that program, here are some small contributions drifting in the ether.

Br Ben Consigli, a Marist Brother currently living and working as a member of the General Council, wrote this excellent article about Marcellin Champagnat and his social/emotional intelligence, highlighting it as a key quality that permeated his leadership.

Br John McMahon, a Marist Brother in Melbourne, and in charge of the Marist Tertiary programs for the Province of Australia, has developed extensive programs and reflections on Marist education and leadership. This article is a more extensive examination leadership models in Marist schools, providing a compelling example of transformational leadership.

Check out the work of our New Zealand compatriots at the Marist Youth office, from the work of the Marist Fathers. They have some interesting resources, information and details about their work in New Zealand. There are two sites of interest. Firstly, there is “in Every Way” which is an online space where people can share the stories, experiences and ideas. Secondly, their “Young Marists” site contains the initial information stop for all things Marist in Aotearoa. Check out their blog on the “In Every Way” website or simply have a look at their work as inspiration on their Young Marists website.

Leadership gatherings in schools are incomplete without practical exercises and scenarios to aid the development process. Check out this website for ideas and games for leadership:

Jacob's Well: Podcasts for Ministry

The summer months are swiftly approaching, and the signs of summer and holidays begin to appear all around us. I thought it might be good to return to some more podcast materials that could be helpful to accompany these coming weeks, refresh the soul with some new listening, or be useful for some summer relaxation. With a focus on faith engagement, these podcasts offer a variety of perspectives for contemporary audiences. As always, the recommendations of these podcasts is not an endorsement of its content, and you are invited to listen with an open and critical ear. Enjoy!

Abiding Together

The Abiding Together podcast “provides a place of connection, rest and encouragement for women who are on the journey of living out their passion and purpose in Jesus Christ.” It is hosted by Sr. Miriam James Hiedland SOLT, Michelle Benzinger, and Heather Kym, who discuss important themes of the spiritual life through conversations with one another, interviews with holy men and women, and seasonal book studies.

https://podcasts.apple.com/au/podcast/abiding-together/id1206416686

Word on Fire

Bishop Robert Barron, the auxiliary bishop of the Archdiocese of Los Angeles, is active in engaging the world through modern media and communication. One of his projects is a weekly podcast on Catholic faith and culture. In the Word on Fire podcast, Bishop Barron shares insights from the greatest Catholic thinkers as well as practical advice for all Catholics trying to live well in their day-to-day lives. A listen for those looking for greater theological content.

https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/the-word-on-fire-show-catholic-faith-and-culture/id1065019039

Another Name for Every Thing with Richard Rohr

I know a number of people in our network are fans of this podcast, so it wouldn’t be a proper resource sharing if it wasn’t included! The podcast is a conversational podcast series on the deep connections between action and contemplation. Richard is joined by two students of the Christian contemplative path, Brie Stoner and Paul Swanson, who engage their real-life experiences, questions and insights with the invitations of the topics of the week.

https://cac.org/podcast/another-name-for-every-thing/

Harry Potter and the Sacred Text

For something a little more obscure and off-the-wall, this podcast has been a favourite of mine for years. Vanessa Zoltan and Casper ter Kuile host a weekly podcast that takes one chapter of a book from J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter series and explores a central theme through which to engage with the characters and context in a unique way. The project originated at Harvard Divinity School, where both engage in the studies of religion. Using traditional forms of sacred reading from several different religious traditions, they offer a refreshing perspective on prayer in a contemporary setting.

Jacob's Well: Sin and Grace

This week’s topic has confounded me for quite some time. Not because I don’t have plenty to say (could I ever been accused of that!?!!), but because it has called me to reflect on the most fitting way to approach it. I wanted to get it right. I wanted it to be good. I wanted it to hit the mark. And, as I hope it will become clear, these desires of mine are the living experiences of the idea in action. This week’s Jacob’s Well lives in that beautiful congruence of page and pathway.

The topic that was suggested to me is, waiting for it, sin. Yeah. Easy, right?!? Not a loaded word at all! The simple question for me to answer is: what is it? So, here is my attempt to navigate this powerful, confusing, and misunderstood idea.

One of the first things we are taught as children is an understanding of right and wrong. This is important, both as an individual who is trying to grow and develop to their greatest potential and as a member of a community where actions have consequences and effects that ripple into the world. Next, the concepts of good and evil are developed, taught, and explained. In this process, all four concepts start to overlap, muddle, and merge. Being right somehow began being good, and all wrongdoing is evil. But what happens if this simplicity is limited? And, in the mix of all this, we find ourselves in the realm of sin. We have equated sin with evil, and it has made all the difference. Our lives become trapped in recognising, judging, and sentencing sin and sinful actions. Something is amiss.

The act of translation is a funny thing. It is not meant to only be an academic or intellectual exercise. These words are the shape of history in action. They are the best ways that people, over time, gave voice to the experience of the deep, the wild, and the confusing. Our words have power, for ourselves and with others. Dumbledore acutely expressed this in his famous statement of the magical wonder of words. The study of words in the Bible is a key tool is working out the core meaning of concepts and ideas that consciously or unconsciously dominate our lives.

The word “sin” appears often in the biblical texts, and, of course, sin is an English word. The common Hebrew term translated “sin” is chait and in Greek the usual word is hamartia. Both terms mean “to miss,” in the sense of missing or not reaching a goal, way, mark, or right point.

Here are a couple of examples of where the word ‘sin’ in biblical contexts makes no sense if the term is understood as doing something evil.

The meaning of the word is usually defined by the context of how it is used. So, for example, In the Book of Judges (20:16), slingers from the tribe of Benjamin are described as being so good with their weapon that they can "aim at a hair and not chait." Could this mean to "aim at a hair and not sin"? It makes no sense. The more logical translation is to aim at a hair and not "miss," i.e. not to hit off target. Another example is in the Book of Kings I (1:21). King David is on his death bed and his wife, Bathsheba, comes to him and says, "If Solomon does not become king after you then Solomon and I will be chataim." Solomon and Bathsheba will be sinners? It means that Solomon and Bathsheba will not reach their potential, will not make the grade, will not measure up. The Hebrew for one of the many sacrificial offering is chatot, from the same root as the word chait. This offering (called in English a "sin offering") can only be brought for something done unintentionally. In fact, if a person purposely committed a violation, he is forbidden to bring a chatot. It is truly a "mistake offering" rather than a "sin offering." These three examples offer a glimpse of the experiences of the early Jewish people and God.

Unfortunately, sin has been weaponised, used as the mechanism that it was never intended to be. As a result, we have been conditionally to believe that the remedy of sin is punishment. It’s not. The remedy of sin is grace. The ever-giving nature of God (the God who is pro-giving, or for-giving) is the balm that heals this ongoing struggle with missing the mark. Sin is the space between what we do in navigating life and who we can be at our fullest and best. At its most foundational, sin is the action of separation from God and others. This is where our freedom is found: always in love, and a decrease in this separation. St Augustine, one of Christianity’s greatest minds, came to the same conclusion: it is our steps away or towards God that defines our whole existence. In our Christian tradition, we know that God understands that we make mistakes, fall short, or even intentionally miss the mark. And yes, there are consequences that require us to address those actions. But we are called to something deeper, to move out of the space of judgment and persecution, and into a space of responsibility, ownership of one’s actions, and to the saving nature of God.

As resources for this week, check out some of Fr Richard Rohr’s reflections on sin and grace (as we know, it just isn’t a MYM resource if Rohr doesn’t get a shoutout?!).

Richard Rohr and Sin: https://cac.org/sin-symptom-of-separation-weekly-summary-2017-08-26/

Richard Rohr and Grace: https://cac.org/grace-is-key-2017-05-08/

Here is a (somewhat heavy) beginning point for accessing St Augustine, as a philosopher: https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/augustine/#Lega

Have a blessed week!

Jacob's Well: The All-Time: Saints, Souls and Hallows’ Eve

This time of year is increasingly fraught with holiday tension. Amidst the growing trend in Australia to mark and celebrate Halloween, this observance is often matched with the catch cry, “It is an American holiday! It is Un-Australian to celebrate it!” or “It is a pagan holiday! Stay away!” I, for one, have been caught in the tension of hiding behind my Halloween embarrassment and my desire to join in the festivities of what is essentially a fun holiday. Far from being an occasion of worshipping the Occult, for most of us, it involves being a justification for eating more sweets and chocolates, watching a scary movie or two, and having permission to wear a costume in public for a couple of days a year (just ask Domenic in the Mascot office: no one will forget that clown costume for a while!)!

In fact, Halloween has its origins in our Christian traditions, and in fact, has scarce connections to non-Christian celebrations. It is commonly known that the day derived its name from Hallows’ Eve, another name for holy or saintly. It is the twin feast days of All Saints and All Souls that came first before the commercialisation of the day transformed it into the macabre and secular (not that there is anything wrong with either!).

All Saints Day is our beginning point. The exact origins of this celebration are uncertain, although, after the legalization of Christianity in 313, a common commemoration of the saints, especially the martyrs, appeared in various areas throughout the Church. The designation of November 1 as the Feast of All Saints occurred over time. Pope Gregory III (731-741) dedicated an oratory in the original St. Peter’s Basilica in honour of all the saints on November 1 (at least according to some accounts), and this date then became the official date for the celebration of the Feast of All Saints in Rome. St. Bede (d. 735) recorded the celebration of All Saints Day on November 1 in England, and such a celebration also existed in Salzburg, Austria. Ado of Vienne (d. 875) recounted how Pope Gregory IV asked King Louis the Pious (778-840) to proclaim November 1 as All Saints Day throughout the Holy Roman Empire. Sacramentaries of the 9th and 10th centuries also placed the Feast of All Saints on the liturgical calendar on November 1. According to an early Church historian, John Beleth (d. 1165), Pope Gregory IV (827-844) officially declared November 1 the Feast of All Saints, transferring it from May 13. However, Sicard of Cremona (d. 1215) recorded that Pope Gregory VII (1073-85) finally suppressed May 13 and mandated November 1 as the date to celebrate the Feast of All Saints. In all, we find the Church establishing a liturgical feast day in honour of the saints independent of any pagan influence.

Along with the Feast of All Saints developed the Feast of All Souls. The Church has consistently encouraged the offering of prayers and Mass for the souls of the faithful departed in Purgatory. Within Catholic tradition, it was held that, at the time of their death, these souls are not perfectly cleansed of venial sin or have not atoned for past transgressions, and thereby are deprived of the Beatific Vision. The faithful on earth can assist these souls in Purgatory in attaining the Beatific Vision through their prayers, good works, and the offering of Mass. The teaching on Purgatory has evolved over time. On 4 August 1999, Pope John Paul II, speaking at a general audience, reminds us of the Church’s teaching on purgatory, said: "The term does not indicate a place, but a condition of existence. Those who, after death, exist in a state of purification, are already in the love of Christ who removes from them the remnants of imperfection as "a condition of existence.” Similarly, in 2011, Pope Benedict XVI, speaking of Saint Catherine of Genoa (1447–1510) in relation to purgatory, said that "In her day it was depicted mainly using images linked to space: a certain space was conceived of in which purgatory was supposed to be located. Catherine, however, did not see purgatory as a scene in the bowels of the earth: for her it is not an exterior but rather an interior fire. This is purgatory: an inner fire." Increasingly, the day is an opportunity to remember our loved ones who have gone before us in death. For me, watching the movie “Coco” is a beautiful example of the unique honouring that can happen on this day.

There are two cultural traditions that I want to draw your attention to is at the congruence of Christian and societal cultures. In the Philippines, in marking the Feasts of All Saints and All Souls, people gather in cemeteries, in ways that is completely unfamiliar to us in Australia. The tradition starts with cleaning the graves and grave markers by pulling weeds and repainting them days before All Saints' Day, a public holiday. On All Saints' Day, a vigil is held, and prayers are said. Families set up tents and stay all day and night at the graves of their loved ones, picnicking with favourite Filipino foods such as chicken and pork adobo, rice, junk food, and soft drinks as if the dead are still among them. For those who cannot make it to the cemetery, they light candles just outside the doors of their homes and make food and alcoholic drinks offerings to their dearly departed in the altar.

In Mexico, All Saint’s Day is celebrated with the first day of the Day of the Dead (Dia de los Muertos), known as “Día de los Inocentes,” honouring deceased children and infants. It is not an occasion for mourning but rather a popular celebration with colourful decoration and a lot of cheerfulness. On these holidays in Mexico, marigolds are everywhere, as people believe this flower attracts the spirits of the dead. People wear the clothes of their departed relatives. They paint skulls on their faces and wear skeleton masks and costumes. Altars are built in homes to honour loved ones. Some even eat and drink the favourite foods and beverages of the departed.

This time is an opportunity to celebrate the legacies and memories of those people who have led lives of faith, hope and love. May it be a time to remember with deep affection and gratitude, and a time of action to keep building our future on goodness, discipleship, and joy.

Jacob's Well: A YouTube Breather

As we hit mid-October, the unforgettable year continues to throw a lot at us all! We can almost see the end of the year coming, and with Christmas bells very quietly wisping in the air, we all need a bit of a breather. Here are some more YouTube distractions/comforters to help you along this week.

Want to visit the great theme parks of the USA but are COVID-stuck!?! The Undercover Tourist provides great high-quality videos of rides, locations, and seasonal decorations from Disney World, Universal Studios, and Hollywood. While they are not the same as the real thing, I found myself with a smile and a bit of an uplift in mood visiting this channel.

Who doesn’t love a movie soundtrack!? Their power to soothe, lift, scare, and grief with us can create a lifetime of memory. Check out Ambient Worlds. They have taken the soundtracks from all of our favourite movies to produce hours of background music, as well as music that fits for seasons, occasions, and moods. I often have them playing while I work, read, or am scrolling through my phone.

Ted-Ed and their Riddles. I know I have shared this channel before, but there is so much to it! One of their richer sub-sources is all the riddles that they have animated and published. I know some of you may find these more frustrating than fun, but they are definitely worth a look and have definite uses in our ministry. One of my favourites is the Infinity Hotel Paradox!

Enjoy these virtual experiences!

Jacob's Well: Anti-Poverty Week

Even before the COVID-19 pandemic made a profound impact on our lives, the pandemic of poverty was already affecting the lives of hundreds of millions of people all over the world, including in Australia. In 2020, just before the government created temporary pathways of reducing poverty, and ignored other growing gaps in wealth distribution, there are more than 3.24 million people, or 13.6% of the population living below the poverty line, including 774,000 children. It is a staggering statistic in a country as wealthy, stable, and socially mobile as Australia. We can often fall into the illusion that poverty cannot exist in a so-called developed country like Australia, but the fact is that it can become more hidden, stigmatized, and deceptive in our great home of the Southern Cross.

Anti-Poverty Week was established in 2002 by the Social Justice Project at the UNSW. It is deliberated aligned to the United Nations International Day for the Eradication of Poverty (October 17), from which it drew its inspiration. The aim of the week is to strengthen public understanding of the causes and consequences of poverty and hardship around the world and in Australia. In addition, the week encourages research, discussion, and action to address these problems, including action by individuals, communities, organizations, and governments.

Here are some great resources to access, in order to complement your existing knowledge, as well as help inform others about its important aspect and reality of our world and our lives, especially our brothers and sisters who are most seriously impacted by poverty, and those who contribute to either its continuation or eradication.

The first place to start is the organization that spearheads the initiative: Anti-Poverty Week, coordinated through a National Facilitating Group, and sponsored mostly by the University of NSW, the Scully Fund, Berry Street, St Vincent de Paul, Life Course Centre, and the Brotherhood of St Laurence. Their website is full of resources, fact sheets, and activities for schools: https://antipovertyweek.org.au/

The United Nations has more resources, information, and initiatives to end poverty that you might think! You could easily fall down a rabbit hole or two investigating all the information that the UN releases! As mentioned, this Saturday 17th October is the International Day for the Eradication of Poverty, and that is running a #endpoverty campaign as part of the day. Start here: https://www.un.org/en/observances/day-for-eradicating-poverty

Check out this article from the Guardian in June of this year, which highlights the ongoing challenges of poverty, its underlying causes and contributors, and the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic: https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2020/jul/11/covid-19-has-revealed-a-pre-existing-pandemic-of-poverty-that-benefits-the-rich

Pope Francis has just completed his latest TED talk, and he remains a powerful voice in highlights the failure of the current economic system. He continues to highlight, as well, the connections between climate change, poverty, and the need to create a more sustainable way of living for everyone, especially the poor who are the ones who feel the consequences of all these realities most acutely. The video is only 13 minutes in length, and definitely worth it. Check it out here:

Jacob's Well: Our Spiritual Songs II

As the seasons change, and times in Australia begin their focus on daylight and sun, I thought it is auspicious to return to a musical interlude for this week’s Jacob’s Well. We all know how music heals, lifts and transforms us. While we are divided by geography and circumstances, music always builds and strengthens the bonds that unite us. Here are some additions to the MYM Corona Comforts Spotify Playlist that might help you through the day. Don’t forget its address: https://open.spotify.com/playlist/3nvlMNqv8D0zr7sO1hqrrE?si=hrH9hy6BRGWu4p-Yi-LWug

OneRepublic- Wild Life

OneRepublic has just released a new song, ‘Wild Life’ and they are stealing MLF’s ideas! Fitting with this year theme, its ethereal reverberation and the iconic vocals of Ryan Tedder offer an uplifting pop song to start the day, or a retreat session!

I Surrender- Hillsong Worship

MYM Sydney has been recommending some great music in the last few weeks with its Music Monday choices. I love them all! ‘I Surrender’ by Hillsong Worship has been on repeat over this last weeks. Consistent in the style of the band and the genre, its slow crescendo-ing draws me deeper into prayer and love.

Meet Me in the Middle of the Air- Paul Kelly

We love this song, especially after ABC’s 7.30 report produced a stunning video of the song with the Melbourne landscapes. Paul Kelly (with the Stormwater Boys) is a music genius and a national treasure! “Meet Me in the Middle of the Air,” is a spiritual song unparalleled in his work, and in the Australian music landscapes. Paul Kelly has a complex relationship with religion, faith and God, but few people could produce a song so poignant, prayerful and moving. Based on Psalm 23, with the emblematic title drawn from 1 Thessalonians 4:17, this song never fails to stir the heart and touch the soul.

Any other suggestions for our spiritual songs collection?

Jacob's Well: Literature from Indigenous Australia

Reflecting on the input from Shannon Thorne from around the Well (from Marist 180, proud Kamilaroi man), one of the lingering thoughts for me is the invitation to keep broadening my education and to listen directly to the voices of Indigenous people in Australia. We can do this in the relationships we build with people in our communities, areas and networks. We can listen to Indigenous elders and voices on our radios, televisions, social media feeds and in written articles and editorials. We can also access the enormous library of books, fiction and non-fiction, that explore historical and contemporary expressions of people’s lives.

Over the weekend, I investigated a number of suggestions for contemporary literature written from Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander perspectives. Here are some of the recommended books to honour the voices, histories and cultures of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. The synopses are taken from other writers who have reviewed these works.

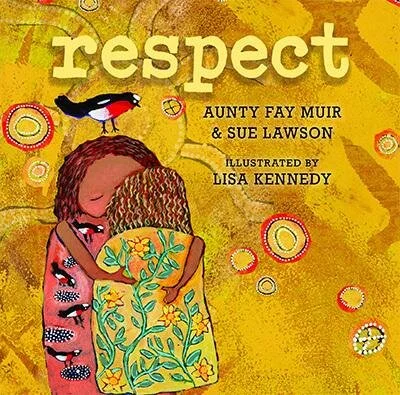

Our Home, Our Heartbeat by Adam Briggs, Kate Moon and Rachael Sarra

Adapted from Briggs' celebrated song ‘The Children Came Back’, this book is a celebration of past and present Indigenous legends, as well as emerging generations. At its heart honours the oldest continuous culture on earth. Readers will recognise Briggs' distinctive voice and contagious energy within the pages of Our Home, Our Heartbeat, signifying a new and exciting chapter in children’s Indigenous publishing.

Finding the Heart of the Nation by Thomas Mayor

Since the Uluru Statement from the Heart was formed in 2017, Thomas Mayor has travelled around the country to promote its vision of a better future for Indigenous Australians. He’s visited communities big and small, often with the Uluru Statement canvas rolled up in a tube under his arm. Here, through the story of his own journey and interviews with twenty key people, Mayor taps into a deep sense of our shared humanity. He believes that we will only find the heart of our nation when Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are recognised with a representative Voice enshrined in the Australian Constitution.

Too Much Lip by Melissa Lucashenko

Wise-cracking Kerry Salter has spent a lifetime avoiding two things - her hometown and prison. But now her Pop is dying and she’s an inch away from the lockup, so she heads south on a stolen Harley. Kerry plans to spend twenty-four hours, tops, over the border. She quickly discovers, though, that Bundjalung country has a funny way of grabbing on to people. And the unexpected arrival on the scene of a good-looking dugai fella intent on loving her up only adds more trouble - but then trouble is Kerry’s middle name. Gritty and darkly hilarious, Too Much Lip offers redemption and forgiveness where none seems possible.

Growing Up Aboriginal in Australia edited by Anita Heiss